2: Parents and lineages

The Tape Piece00:00

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s working.

Steve Paxton So, let me start again.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton There's a typist who's typing what they hear. What they hear is coming from a tape machine which is beside them on the stage. The person who is running the tape machine so that the tape machine doesn't go too fast for the typist is the dancer. So the dancer can only dance when the typist doesn't need rewinds or pause or something done to the tape machine. So the dancer is dancing, and then the typist says, It's going too fast, you know, and so the dancer has to stop dancing and go be the technician. And so this was the setup. […]

Myriam Van Imschoot What would have been on that tape?

Steve Paxton I don't remember.

Myriam Van Imschoot Really?

Steve Paxton I don't think it mattered very much. It was just words.

Myriam Van Imschoot And the typing is in fact transcribing what's on the tape. What's already pre-recorded on tape is getting re-typed. It’s getting typed. So, he's not typing what he sees on the floor or…

Steve Paxton No, no, he’s transcribing a tape.

Myriam Van Imschoot He's just transcribing that tape. Okay. So that…that's a speed constraint. It's mainly working on like a kind of time.

Steve Paxton Time and phrasing. Because if the typist needs the tape rewound to get a few words, the dancer has to come and do it. So the dancer is controlled by the typist. And he’s only free to dance when the typist is typing easily the words on the tape. The words on the tape are… Maybe one reason I can't remember them is because they would have been rewound and played several times, and one would have lost a sense of flow, but you would have had a lot of images repeated and corrected.

Myriam Van Imschoot Jesus. That’s a good time, you know, it’s…it’s brilliant.

Steve Paxton It's not brilliant. But it's…it's not bad. It means the dancer can’t go on an ego trip and get lost in their own movement kind of thing or just be related to the words because the words are going to be, you know, constantly being manipulated.

Myriam Van Imschoot That’s what one would call indeterminate movement.

Steve Paxton Well, it’s a structure which makes it [a] kind of indeterminacy. Yeah. So, the dancer…whatever assumption you have about improvising is going to be broken. Because you’re going to have to stop doing it and become a functionary in the situation as opposed to the dancer.

Myriam Van Imschoot And improvisation relates to the dancing. Well, of course, the whole setup, but you were also improvising your movements.

Steve Paxton Yeah. [with feigned ostentatious pride] My first handstands on stage!

Myriam Van Imschoot Oh God.

Steve Paxton Yeah, turning upside down and…

Myriam Van Imschoot Rewind!

Steve Paxton Yeah.

The question of improvisation03:10

Myriam Van Imschoot What made you do that piece?

Steve Paxton Because I was getting interested. I was getting bitten by the improvisation bug. But by 1970, I had decided that I'd spent 10 years making structures with scores like this, in which dancing is somehow determined but not necessarily shown or overly aestheticized. And I had thought, Well, maybe my next decade will be, you know, I should stop this approach and just look at improvisation because I don't know what it means, and the only way to find out is to define it for myself.

Myriam Van Imschoot What were your initial questions when you enter that room…

Steve Paxton The room of improvisation?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah!

Steve Paxton The initial questions…

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, some questions that made you do it in the first place.

Steve Paxton What does this word mean?

Myriam Van Imschoot Really? There was already this consciousness of…

Steve Paxton What does this word “improvisation” mean? I don't know what it means in the same way that I didn't know what “democracy” meant. I didn't know what improvisation was. And it was at that time, about '72, these two ideas came together in Contact Improvisation, where the democracy is available because of the improvisation. And the improvisation is there in the way that it is in a conversation with words. We have essentially a conversation with movement and all that that proposes…all the possibilities of movement that you could do because you're dancing with somebody who will support you or whom you must support. And again, a mechanism in which you don't determine your own way. So, the ego is a bit subverted. It has to exist in a different way in the performance than had traditionally been the case and where you had a structured improvisation, so that you could look at that structure and see sort of how improvisation worked, as opposed to a word which had virtually no definition and so anything that wasn't…it was a… Yeah, it was the vast wasteland outside of the high tower of choreography and movement composition and the way it had to happen.

Myriam Van Imschoot I'm so happy to hear that a question made you go for it in the first place. You know, what is it? What the hell is it? Because in many practices, the improvisation gets employed or people do it, but there's like a fairly vague interest in addressing it as such, you know what I mean? It wouldn't necessarily be that people improvising would actually ask the question you were asking.

Steve Paxton I think the question didn't seem very strongly posed in my dance student and early dance profession era. I didn't hear anybody else asking what it was.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, that's what I was wondering. I mean, just that, in fact. Yeah.

Steve Paxton It didn't seem to be a big question. There was an assumption that it was whatever was not choreographed. And another assumption that I remember from that particular era in that place was that it was emotional, enacting your emotions.

Myriam Van Imschoot That may have been because of some theater improvisations going on in the 60s too that were much more tapping for emotional resources, probably even like a modern…

Steve Paxton I think also that existed in the dance.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, the modern dance tradition has its link with improvisation, too, but there it would have been more psychologically…

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot …charged with psychological meaning.

Steve Paxton Yeah, the Open Theater and Second City were into working with improvisation almost as a kind of challenge for the actors. But again, trying to get beyond the playwright and into interacting and making images on the spot. I don't know why this is so interesting to us. But we do have a kind of fascination with it in a lot of spaces.

Abstract expressionism and gestural spontaneity08:17

Steve Paxton …I mean, look at the art that was happening in the 50s. I mean, what was Jackson Pollock doing?

Myriam Van Imschoot He was improvising.

Steve Paxton Apparently, I think one could say that was paint improvisation. And de Kooning and Kline, you know, indeed, how about going back to Chinese calligraphy? Does… It sounds like, when you hear it described, there's a kind of open mind about getting it just right. It has to be open minded. It can't be too well known or else it’s not as interesting as the kind of accident…accidental perfection that you get from coming from another place. Maybe that's what we're looking for — both the accidental and the perfect. Yeah, perfectly appropriate gesture at any one moment.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. With abstract expressionism there is very often the use of words that relate to improvisation - in terms of, like, gestural spontaneity.

Steve Paxton Action painting.

Myriam Van Imschoot Action painting.

Steve Paxton Yeah, exactly. It was a dance in front of a canvas with a brush and with a certain picture plane that you had to work against.

Myriam Van Imschoot For example, there was, like, a book that tried to make like a…

Steve Paxton But accidents were accepted.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, and they were not erased. The result of it was just what the process had been. And you would have a huge sense of process.

Steve Paxton You look at Kline and de Kooning for two masters of that form and you see that there is another mind at work here. This is not pointillism anymore. This is not surrealism. This is not any of those much more conditioned and perfected techniques. This is something that's unique to this one person, and they’re the person who does it best. All the de Kooning imitators somehow don't have quite that unique quality that de Kooning himself had. But I mean, he was making it up and they were copying. And in a way, the performance that we saw last night, Lisa [Nelson] described as an imitation of improvisation, and the derivative painters were doing imitations of action, really. And although they might feel it as deeply as they could feel it, they weren't feeling it in the unique way that the originators of the various forms felt that. They weren't in the position of being both originator and artist. They're there. So, they're considered secondary artists. This is an honorable space, and one that many of us have lived through, you know, in various ways, and might have to resort to later on, who knows. But it's a space where you're manipulating the known requirements of the art in…and trying to create new possibilities with known materials.

Myriam Van Imschoot But what…

Steve Paxton It’s a craft as opposed to the kind of art that we're talking about.

Myriam Van Imschoot I was just having this flash of an idea: the thing with abstract expressionism, there is a strong link to improvisational values or just the way improvisation works. I think we agree on that. But in the beginning of the 60s, there was more and more an attack on abstract expressionism, and with that attack…well, I'm saying beginning of the 60s to fine-tune it…

Steve Paxton Could you just name…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, for example, Robert Rauschenberg.

Steve Paxton Ah! For instance, I knew it. And Jasper Johns, right?

Myriam Van Imschoot Jasper Johns and Frank Stella and Andy Warhol and the whole generation.

Steve Paxton John Chamberlain.

“In Factum I and Factum II Rauschenberg investigates the distinction between spontaneity and accident in making a work of art. He emphasizes this distinction by reiterating the effects and images in both paintings. Each work is the product of careful choices and a deliberate process in which, however, an element of the spontaneous and the accidental is maintained. The aesthetic redundancy and pairing of the two works, reinforced by the internally paired images in each “Factum,” provoke the viewer to look again at what is presumably the same image.” National Collection of Fine Arts, Robert Rauschenberg, Smithsonian Institution, City of Washington, 1976, 93. ↩

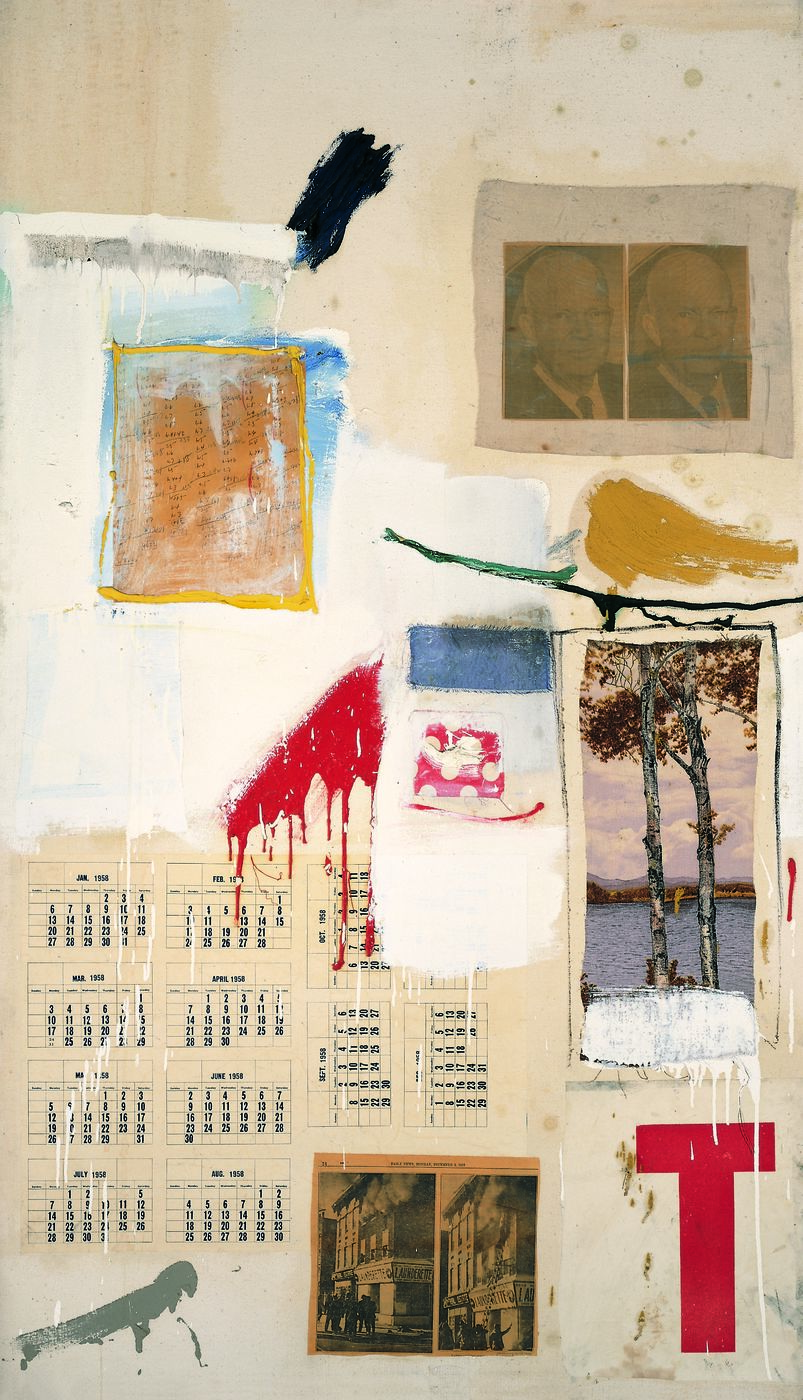

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah! Go ahead! Very interesting work in that respect is Factum I1 and Factum II of Robert Rauschenberg, and the I is like a perfect action painting. I mean, it's…

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot He made it in the methodology of the abstract [expressionists].

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot And the second one, Factum II, is an exact copy of the first one. The first one was spontaneous, and it all came very spontaneously, and so on. And the second one would be like an exact copy.

Robert Rauschenberg, Factum I, 1957, Combine: oil, ink, pencil, crayon, paper, fabric, newspaper, printed reproductions, and printed paper on canvas; 61 1/2 x 35 3/4 inches (156.2 x 90.8 cm), The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, The Panza Collection, ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Robert Rauschenberg, Factum II, 1957, Combine: oil, ink, pencil, crayon, paper, fabric, newspaper, printed reproductions, and printed paper on canvas, 61 3/8 x 35 1/2 inches (155.9 x 90.2 cm), The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Purchase and an anonymous gift and Louise Reinhardt Smith Bequest (both by exchange), ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Steve Paxton Now one wants to know how he made these.

Myriam Van Imschoot You know? Probably you know.

Art historian Jonathan T.D. Neil analyses Factum I and Factum II as follows: “To say that II was painted after I would be incorrect. The two canvases were painted simultaneously, with Rauschenberg attending to one and then to the other. We should note, however, that he did not replicate his actions and materials in order to make the same painting, or even really to make two different paintings; rather, Rauschenberg seems to have painted the works simultaneously so as to render difference itself, to render difference as an inescapable, indeed necessary, goal of creation, artistic or otherwise.” Jonathan T. D., Neil, “Factum I Factum II.” in Modern Painters, Dec. 2005–Jan. 2006, 76–77. ↩

Steve Paxton I don't know, actually.2 No, the question just comes to mind. What I think he probably did, but I don't know how I know this, so this isn't a fact, this is just a guess, really, is that if he made that kind of yellow horizontal stroke, and it dripped in a certain way…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes, yes.

Steve Paxton …that he would then, with the muscle memory, do the same gesture on the next canvas at the same time, so you would then have the two yellow lines established and build in that way. Or, do you suppose that he finished one completely, and then went on to try to have the same accident again, you know what I mean.

Myriam Van Imschoot That’s the way I always thought it was.

Steve Paxton We must ask him.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, I don't know if he's an accessible person to ask that sort of…

Steve Paxton He is…I mean, deeply shielded from people like us, so that he won't be bothered too much, but I bet he would be…I don't know, or maybe somebody has asked him already and you can find it in art history someplace. How exactly did that happen? Probably the first way would be the most…

Myriam Van Imschoot …likely…

Steve Paxton …likely scenario, but…

Myriam Van Imschoot Anyway, just that piece was felt as a criticism on this whole notion of the unique and of you know…

Steve Paxton …the spontaneous.

Myriam Van Imschoot The spontaneous and so on and probably, from then on, you see more and more criticism in that vein somehow, and then you would have like a resistance towards the handmade or anything — the mechanisation of the making of a painting and stuff like that. So that was telling in some way because in visual art at that moment, they are actually moving away from many things that, I mean, things that I relate to improvisation, and I was just wondering whether it was like…whether in the air was more like a general criticism on that whole package somehow that made people feel not interested in it as much. You know what I mean? I just make an assumption from what happens in the visual arts.

Generational struggles15:23

Steve Paxton Well, I think…oh god, I think it's a very destructive viewpoint, Myriam.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, well.

Steve Paxton Destructive in the words that you’ve used: attack and criticism and all of this, I mean.

Myriam Van Imschoot Maybe it’s more playful, yeah.

Steve Paxton I think, in a way, it's the struggle for the young artist to achieve any kind of…

Myriam Van Imschoot …space?

Steve Paxton Stature, not just space, not just selfhood in the art form or something like that, which is all an issue.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton But actual[ly]…if your hero… I have this problem with Cunningham. Not a problem. I'm using that same kind of word. I have this relationship to Cunningham.

Myriam Van Imschoot I'm contaminating you.

Steve Paxton [laughing] No, no, the world does this. The world suddenly turns everything into battles. And I don't think that's… Again, this is something that needs to be questioned. It doesn't need to be like that, but I had that relationship to Cunningham, and I began to realize that in my art form of dance, which is, whatever it is that's not classical, and in which invention is prized…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton …that… Well, I exist in modern dance. We just had 100 years of it. So we have a pretty good look at how a new thing becomes available in the culture. And what we see is that in the historic names, the names of artists that we have prized in this form, that they did not do what they were taught. So, in other words, you look at Cunningham, you know, who I have that relationship with, the person he had it with is Graham. He did not produce…reproduce Graham in technique or in aesthetic. Graham did not reproduce Denishawn. Denishawn did not reproduce Duncan. And God knows what Duncan didn't reproduce! She didn't reproduce ballet, obviously. But, in other words, what we are given in order to fulfill that kind of lineage — you have to not do what happened before — which implies a certain amount of struggle to get away. I mean, we're creatures of habit. That's underlying, underlaying everything that we have said. We are creatures of habit, and we have to question our own habits and the habits of the culture. And so, you do that by a certain amount of reproduction and comment to yourself like, No, I don't want to point my toe. You know, what can I do?

Myriam Van Imschoot It can be the details. I mean, just to be sensitive to…

Steve Paxton Yeah, I don't want to be working with diagonals and circles and, you know, lines of people and arabesques, you know, on and on and on. That's done. We have enough of that, you know, not enough in the sense that it should stop, but enough that we don't need to flood the market with yet more arabesques. We have beautiful arabesques already. Do we need, you know, that? So, yeah, the question is what do we need? And so, it's a philosophical journey in a way and a survival question. And I don't know how art helps us survive except it seems to me to make a lot of things worthwhile and give us a kind of space to operate in that’s not about hitting somebody over the head for their lettuce and stealing their lettuce away to feed our family, you know, kind of thing. We've managed to get beyond that basic struggle for existence and gotten to some place where we can start looking at phenomena and relationships on a different level. So, it seems maybe it has a survival virtue.

Myriam Van Imschoot Of course, I mean, I really want to reform[ulate] it - what was just said.

Steve Paxton Okay.

Myriam Van Imschoot Anyway.

Steve Paxton So, anyways, back to Factum I and II.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton Is perhaps Rauschenberg questioning the premises that he was handed?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes, and that puts other ideas central, somehow. I mean, that's a successful gesture or move or something that displaces art.

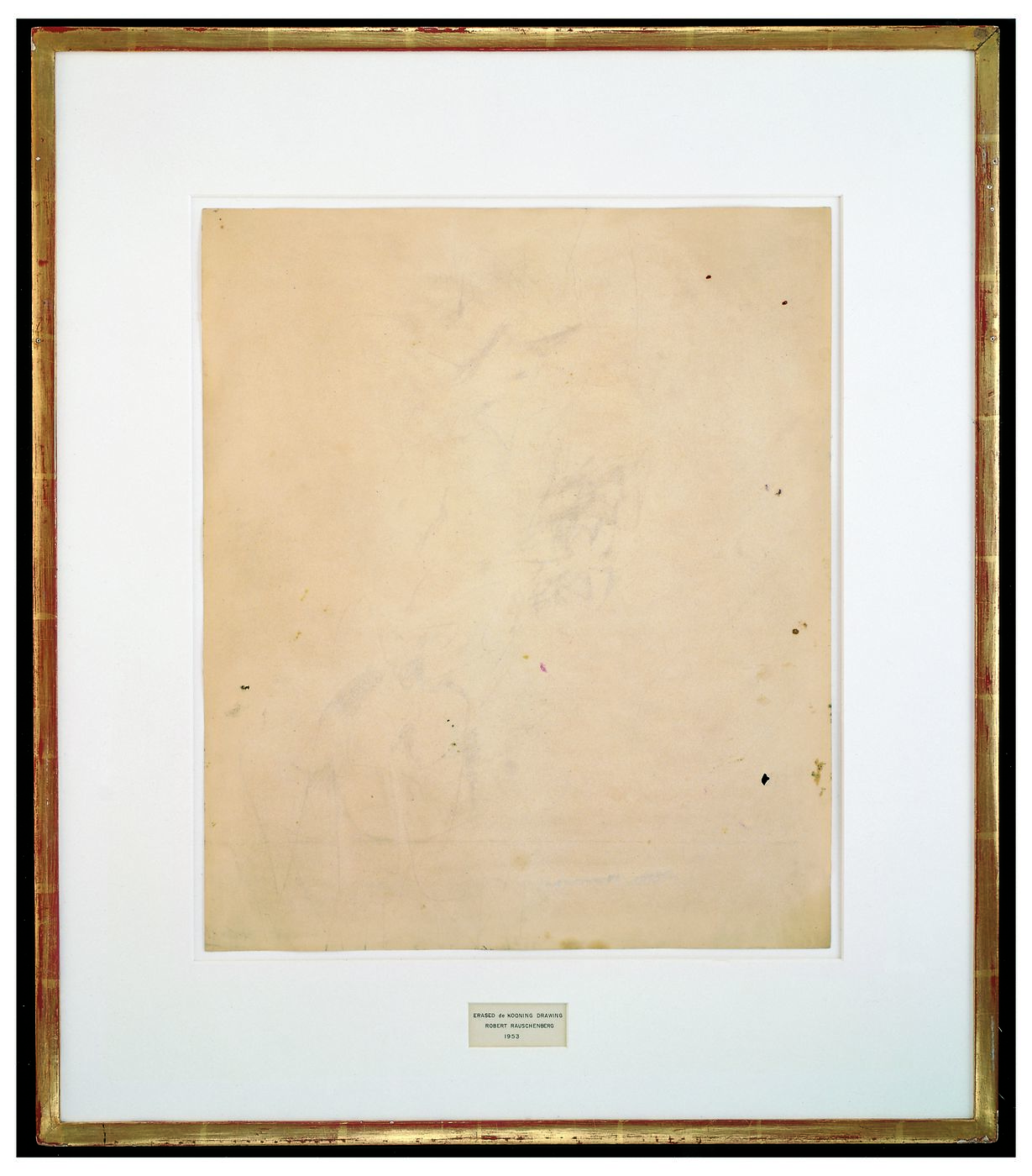

Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) is an early work by Robert Rauschenberg. It investigates the possibility to produce an artwork merely by the gesture of erasing another one. As the base for this work, he used a drawing from the Women series by Willem de Kooning, at the time one of the most venerated abstract expressionist artists. Recollecting how Rauschenberg asked de Kooning for the drawing he says: “I bought—I was on a very low-budget situation. But I bought a bottle of Jack Daniels. And hoped that— that— that he wouldn’t be home when I knocked on his door. [laughter] And he was home. And we sat down with the Jack Daniels, and I told him what my project was. He understood it. And he said, “I don’t like it. But, you know, I—I understand what you’re doing.” And— and so—He had a painting that he was working on, and he went over and— and—and put it against the— the— the— the door to the stairs. And as though, you know, being closed wasn’t enough. By now, [laughs] I’m really frightened. And— and—and—and he said, “OK. I don’t like it, but I’m—I’m going to go along with it, because I understand the idea.” And—He went through one portfolio, and he said, “No. It’ll have to be something that—that I’ll miss.” So I’m—I’m—I’m, you know, just sweating, shitless, ya know? And then I’m thinking, like—like, It doesn’t have to be something you’re gonna miss. [they laugh] And—and then— and then—Then he went through a second portfolio. Which I thought was kind of interesting, things he wouldn’t miss and things he would miss and—And then— and—and he pulled something out, and then he said, “I’m gonna make it so hard for you to erase this.” And he had a third portfolio, that was—that had— had—had—had crayon, pencil, charcoal and—and—and—And it took me about a month, and I don’t know how many erasers, to do it. But actually, you know, on the other side of this is also—I mean, if there’s ever any question about this, there’s a gorgeous drawing of Bill’s.” Robert Rauschenberg, video interview by David A. Ross, Walter Hopps, Gary Garrels, and Peter Samis, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, May 6, 1999. Unpublished transcript. ↩

Steve Paxton He also erased de Kooning…3

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes. Yeah.

Steve Paxton …you know, so he had a relationship with de Kooning. He erased de Kooning, and the reason he erased de Kooning as opposed to anybody else is that he had this relationship with de Kooning. de Kooning was his…was doing something that fixated him and he had to question it. And so you could say it's an attack, but I think it's more of a relationship. It's more like father and son. How do you get away from your parent? And even if, in the art world, you kind of make up who your parent is, you know, like, Merce was my parent, you know, among many, but he was definitely the prime parent. And the one I then couldn't emulate even though he was my main teacher, and he brainwashed me with technique and aesthetic of his, you know, and I was a willing passive tool to do whatever he wanted for all those years. Then, having been given all these new habits that are Cunningham habits, how do I find once again the Paxton world, you know, which never was developed anyway because I was too young. I didn't really have one, didn't have a thought in my head, of course, so I had to develop some thoughts, didn’t I?

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, Traces of drawing media on paper with label hand-lettered in ink, and gilded frame, 25 1/4 x 21 3/4 x 1/2 inches (64.1 x 55.2 x 1.3 cm), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis, ©Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton And to be as good as Cunningham, my rival, I had to develop a whole new aesthetic. Look what he did. Well, I've got at least, in fact, some techniques and a whole new worldview.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, you managed pretty well.

Steve Paxton Well, but I had such a good teacher.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton [laughing] So rivaling your teacher seems to me a very interesting place, when sometimes you rival the whole aesthetic. I think Yvonne went the route of challenging the whole aesthetic and trying to create yet another worldview. But it's very creative, all this interplay. Because look, out of this you get a David Gordon, a Trisha Brown, a Steve Paxton, a Yvonne Rainer, and a number of other people, and then the people who accepted them as kind of artistic parental figures rival them and you get, you know, it just [goes] down through the ages. You get these relationships, which are both extremely affectionate and loving and at the same time trying to create not only the climb up that long slope, you know, that mountain, but trying to create the mountain that you're climbing as well, you know. It’s a…it's a big…a big event. And then there's another level where you accept all that training and you say, “What have I, you know, put this last 10 years into, anyway?” I've been here studying this person, and I'm going to take their work onwards, and then you are somebody who creates the new manifestations of an already established order. Those are both extraordinarily… One is the refinement of design or the new possibilities for in the design world, and the other is the invention of new areas to design with. [laughing]

Cunningham's Story and indeterminacy23:08

Story (1963) is a piece by Merce Cunningham and premiered on July 22, 1963, at UCLA, California. The set was designed by Robert Rauschenberg and the music was composed by Toshi Ichiyanagi. Shareen Blair, Carolyn Brown, Merce Cunningham, William Davis, Viola Farber, Barbara Lloyd, and Steve Paxton were part of its original cast. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot Within the Cunningham work and area, I was very interested in a particular moment or field of work and that's right about 1963 when Story5 was initiated. According to the David Vaughan book,…I'm basing myself a lot on the details in there.

Steve Paxton It’s a great calendar.

Myriam Van Imschoot It's just so useful and also, because it's so…you know, he doesn't interpret a lot. He just gives a lot of data, and it’s good.

Steve Paxton Yeah. It’s basic.

Myriam Van Imschoot Just before Story, the way he is situating that is that he [the Cunningham Company] has this residency in California.

Steve Paxton UCLA?

Myriam Van Imschoot Wait a minute. I made some notes.

Steve Paxton UCLA, living at Malibu.

Myriam Van Imschoot So you were, at that point, you were part of the company?

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, it’s here. So that June, that residency, something important happened somehow within the larger context of Cunningham's work at that time because he started trying to see if he could initiate a greater degree of indeterminacy than he ever had tried before, and David Vaughan calls it the closest he ever came to permitting improvisation.

Steve Paxton Well, we have to go back to that question that you raised earlier about improvisation being…

Myriam Van Imschoot …perspective.

Paxton and Van Imschoot discuss “perspective/perspectival” in the first section of this interview cluster as well. ↩

Steve Paxton It’s perspective.4

Myriam Van Imschoot But anyway, even within that moment.

Steve Paxton It's true. Well, actually, what he was allowing was indeterminacy because the movement was all set and what we could do was change the amount of time each element took. We also could put it anywhere in the space that we wanted to. But we could not invent movement.

Myriam Van Imschoot No, no. It was like a sample that was already there for you like a section?

Steve Paxton Yeah. You had a phrase.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. And you could, you know, choose order, sequence, maybe length a little bit?

Steve Paxton You could. You had many phrases, but you couldn't change…could you?

Myriam Van Imschoot …the internal unit of that phrase.

Steve Paxton I can’t remember whether you could or whether you could do more of, you know, like, if you had a hop, if you could hop 15 times instead of three times. I can't remember.

Myriam Van Imschoot I don't think…

Steve Paxton I don't think you could. But maybe…

Myriam Van Imschoot I don’t think it was movement-related. It was more like, where you put it into a performance.

Steve Paxton Yeah, where you chose to draw it in space.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah and maybe the length of it, things like that. Doesn't seem that he would release the possibility of movement.

Steve Paxton Well, that's really his job. He's the choreographer.

Myriam Van Imschoot I mean, it would be very surprising if he did, but…

Steve Paxton I don't think he could make that step, and I don't think John could either…Cage. I don't think they were thinking in that way. They were interested in not knowing, not pre-determining.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton They were interested in that space, not pre-determining where these elements occurred. But in terms of what they…what John did with musicians and what Merce did with dancers was to give them materials that they could then put anywhere in the time or in the section in the overall piece.

Myriam Van Imschoot I was wondering was it…was it an issue in the company at that time?

Steve Paxton In what way?

Myriam Van Imschoot That greater degree of indeterminacy and would they have to use the word improvisation somewhere in there?

Steve Paxton No. I don't think we would have used the word improvisation for that.

Myriam Van Imschoot Because I was surprised that David Vaughan used it.

Steve Paxton Well, it's a step in that direction of loosening up the overall structures that were the norm in that time.

Myriam Van Imschoot Was that…

Steve Paxton Nobody else had that kind of freedom except, in fact, we found…you find out much later, you know, Freedom of Artistic Information Act or something, that Balanchine would sometimes allow dancers, certain dancers, Suzanne Farrell, to improvise material but which she then had to reproduce.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, and set.

Steve Paxton So, but she was allowed that or Graham dancers, just from Graham’s own ineptitude as a choreographer, did a lot of the work of choreographing or determining materials, you find out from various people later. So, but that wasn't what the public was understanding of the work. They thought that these were the growths of not just seeds that the choreographers planted but carefully tended all the way up to the blossom of performance by the choreographer.

Myriam Van Imschoot The audience accepts what it’s being told.

Steve Paxton Well, it's being told all these cold generalities. It doesn't really matter what the details are or how something got some place. I mean, in every area of invention, you find out later that actually, Buckminster Fuller didn't invent tensegrity structure, some student did. […]

Steve Paxton Putting, making an issue of it was pretty much my generation’s job, I think. […]

Myriam Van Imschoot To come back to Story, is it true that that was put out of repertory because the dancers didn't like it?

Steve Paxton Story?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, because they felt that the freedom was just too constrained and there were so many…

Steve Paxton I don't know because I left the company while it was still in repertory. I know that certain performances Merce didn't like very much because the dancers made use of freedom that he didn't approve of.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, there was this tension around potential freedom to what extent.

Steve Paxton Yeah, and he mainly demonstrated. It didn't become a philosophical issue. It was an emotional issue. Just after the performance, when he went into his dressing room and slammed the door and didn't come out for two hours, you realized that he didn't like something.

Myriam Van Imschoot He wasn’t very communicative.

Steve Paxton No, he either wasn't able to deal with a company on that level or maybe he felt like although he didn't like those permissions or those freedoms taken, he couldn't really argue with the fact that he'd set up a situation in which they were possibilities, and he hadn’t envisioned those possibilities. And so they were outside the realm of what he wanted in the piece.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, according to David Vaughan, he felt that the reason why Merce Cunningham, you know, put his toe in that water was because there was a pressure in his surroundings to more and more release control. So that, and according to Vaughan, he doesn't approve really of those experiments. He thinks that Merce Cunningham, somehow, wasn't true to himself. I mean, he said, “Okay,” by doing…

Steve Paxton …by doing it?

Myriam Van Imschoot …by doing it. That there was, somehow, some pressure in the cultural milieu to…

Steve Paxton Well, it's true that Yvonne Rainer had produced a dance but, you see, we could work much faster than Cunningham could. Cunningham had this giant machine to manipulate and repertory to keep up and tours to go on. We didn't have tours, and we didn't have repertory, so we could work more at the frontier, and yeah, it was a period when the individuality of the performers was more up for questioning than had previously been the case.

Myriam Van Imschoot Which pushed him into trying several things, but he left it because it just didn't fit.

Steve Paxton It wasn't his art form. No, he had an art form already going just fine, and he's continued it quite successfully. So I don't think he's interested in these questions as possibilities.

-

“In Factum I and Factum II Rauschenberg investigates the distinction between spontaneity and accident in making a work of art. He emphasizes this distinction by reiterating the effects and images in both paintings. Each work is the product of careful choices and a deliberate process in which, however, an element of the spontaneous and the accidental is maintained. The aesthetic redundancy and pairing of the two works, reinforced by the internally paired images in each “Factum,” provoke the viewer to look again at what is presumably the same image.” National Collection of Fine Arts, Robert Rauschenberg, Smithsonian Institution, City of Washington, 1976, 93. ↩

-

Art historian Jonathan T.D. Neil analyses Factum I and Factum II as follows: “To say that II was painted after I would be incorrect. The two canvases were painted simultaneously, with Rauschenberg attending to one and then to the other. We should note, however, that he did not replicate his actions and materials in order to make the same painting, or even really to make two different paintings; rather, Rauschenberg seems to have painted the works simultaneously so as to render difference itself, to render difference as an inescapable, indeed necessary, goal of creation, artistic or otherwise.” Jonathan T. D., Neil, “Factum I Factum II.” in Modern Painters, Dec. 2005–Jan. 2006, 76–77. ↩

-

Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) is an early work by Robert Rauschenberg. It investigates the possibility to produce an artwork merely by the gesture of erasing another one. As the base for this work, he used a drawing from the Women series by Willem de Kooning, at the time one of the most venerated abstract expressionist artists. Recollecting how Rauschenberg asked de Kooning for the drawing he says: “I bought—I was on a very low-budget situation. But I bought a bottle of Jack Daniels. And hoped that— that— that he wouldn’t be home when I knocked on his door. [laughter] And he was home. And we sat down with the Jack Daniels, and I told him what my project was. He understood it. And he said, “I don’t like it. But, you know, I—I understand what you’re doing.” And— and so—He had a painting that he was working on, and he went over and— and—and put it against the— the— the— the door to the stairs. And as though, you know, being closed wasn’t enough. By now, [laughs] I’m really frightened. And— and—and—and he said, “OK. I don’t like it, but I’m—I’m going to go along with it, because I understand the idea.” And—He went through one portfolio, and he said, “No. It’ll have to be something that—that I’ll miss.” So I’m—I’m—I’m, you know, just sweating, shitless, ya know? And then I’m thinking, like—like, It doesn’t have to be something you’re gonna miss. [they laugh] And—and then— and then—Then he went through a second portfolio. Which I thought was kind of interesting, things he wouldn’t miss and things he would miss and—And then— and—and he pulled something out, and then he said, “I’m gonna make it so hard for you to erase this.” And he had a third portfolio, that was—that had— had—had—had crayon, pencil, charcoal and—and—and—And it took me about a month, and I don’t know how many erasers, to do it. But actually, you know, on the other side of this is also—I mean, if there’s ever any question about this, there’s a gorgeous drawing of Bill’s.” Robert Rauschenberg, video interview by David A. Ross, Walter Hopps, Gary Garrels, and Peter Samis, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, May 6, 1999. Unpublished transcript. ↩

-

Paxton and Van Imschoot discuss “perspective/perspectival” in the first section of this interview cluster as well. ↩

-

Story (1963) is a piece by Merce Cunningham and premiered on July 22, 1963, at UCLA, California. The set was designed by Robert Rauschenberg and the music was composed by Toshi Ichiyanagi. Shareen Blair, Carolyn Brown, Merce Cunningham, William Davis, Viola Farber, Barbara Lloyd, and Steve Paxton were part of its original cast. ↩