1: On Improvisation

The Tape Piece00:00

Steve Paxton […] So, this is improvisation day, and we're talking about the first solo I made, which was…which I considered improvisational. I don't recall the name of it. It was in 1967. It was for a tour that I made of the West Coast, and it was a text, which was being typed, was being…wait a minute. It was being produced on a tape machine for the audience and the typist and was being typed. And whenever the text got ahead of the typist, the typist would tell me, and I would come and rewind the tape for the typist and start it again. And whenever I wasn't involved with this duty, I was free to dance and improvise, and all I can remember was that I stood on my hands during that improvisation. I danced around in a - I think - a kind of Cunningham-like way because that material was still very strong in my body, that technique, and I think it was about 12 to 15 minutes long all together.

And as I have said many times, what I…why I started working with improvisation, I had seen improvisation, I had been impressed with some improvisations that Trisha Brown and Simone Forti had done - for instance - in the Judson workshop, really more than any, strongly impressed, and was very intrigued with the idea, but I didn't feel like I knew what it was they were doing. I didn't feel in the way that I felt more secure with thinking about technique and dance aesthetics of that time, I didn't understand what I was supposed to do if I was improvising. I had studied with a man named Eugene Lyons, who was actually a kind of friend, a director who was interested in working with improvisation. We did some workshops, a series of workshops, with other dancers trying to improvise, but the premise of that improvisation was things like… You would take a theme like self-sufficiency or security, and you would improvise that, you know, so I didn't, it didn't help. It wasn't helpful in illustrating what the word might mean.

As I think is pretty clear, I wasn't a great fan of jazz or other improvisational forms where improvisation might be found, nor did I understand classical music and its relationship to improvisation. And there was no improvisation in Cunningham or in Cage although they employed forms, which required choices, it was not considered improvisational. So, the word floated there really in abstraction, and I had no idea what it was. And I began trying to do it. I simply set out to try to do something and see if I thought it was improvisation. So, it was at a very low level of theory that I began and… But eventually, in that solo, and with trying to define the word in action, I came to accept what I did as improvisation to some degree although, again at a very low level, and began to see the possibility of other higher degrees of improvisation.

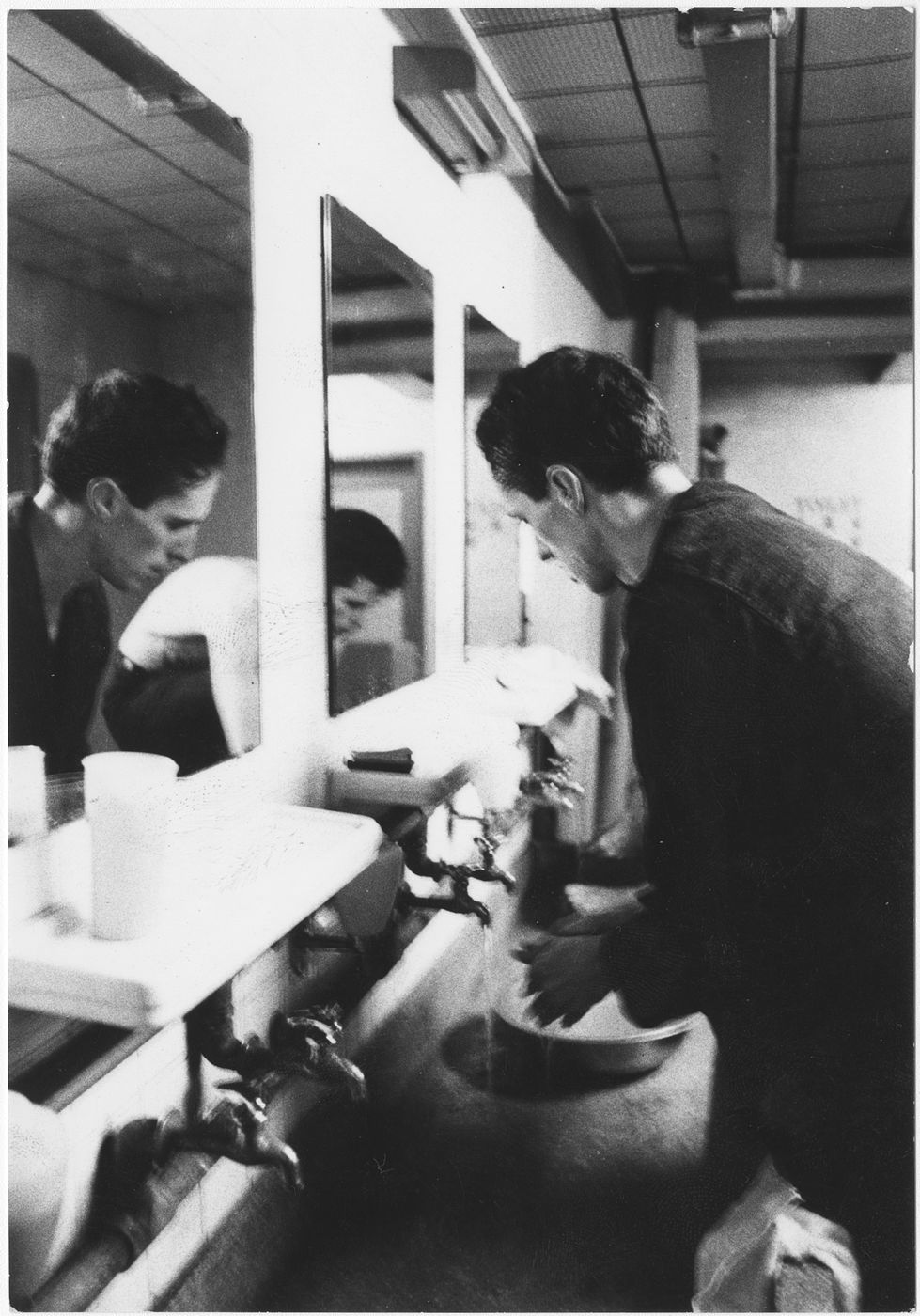

Steve Paxton washing hands, probably during Cunningham Dance Company World Tour. Photograph Collection. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York. Photo: Unattributed, 1964.

So, as for defining the word, I defined it in a much later article as improvisation is a word which, in which the subject is constantly changing, the actual attributes of improvisation are not fixed. So, we have words like this in which the definition is a changeable one. I can think of other such words that we use, freedom for instance, would mean something different to every person. God would mean something different to every person. Love would mean…would be very specific. So, this is a category of words. Improvisation is one of those words.

Myriam Van Imschoot Do you remember what you found out about it - about that word - during the solo?

Steve Paxton I think I've just described it. I found out not very much. I found out a little bit though, and I found out, I felt like I had found…I found out what I thought by doing it, by trying to do what I thought the word meant, which was simply not the plan, you know, I ended up noticing that I more or less improvised a selection of movements, recognized some of those movements as being my technical…

Myriam Van Imschoot …repertoire?

Steve Paxton …repertoire. Yeah. And some of them not, you know, that I, for instance, I mentioned standing on my hands because that was not something Cunningham would have done, you know. So, but at the same time, I'm sure that my toes were pointed most of the time, you know, kind of the habits that you're in. My arms were used in a certain way. I probably used my torso in a Cunningham-like way. So, I recognized that I had a collection of habits and made me see that, that were there underneath my will. That if my will directed me in space, or to move a certain part of my body, it was apt to be in the style of something that I already knew. And that had been given to me as a piece of dance to learn, you know, or a technical piece of the dance equipment. And so it had been defined as dance, so there was not much chance at that stage that I could have done something - improvised movement - that was not technical, and I had a prior definition as dance material. I don't think I would have been doing anything very surprising with my body. It was perhaps a little bit surprising that, you know, this form that I created showed that my dancing was to be stopped by another event, you know, the rewinding of the tape machine, and… So, it sort of illustrated that it was being improvised and that I was… The dancing, the movement, which is meant to be the subject of a dance was actually subject to something else, subject to another process.

Myriam Van Imschoot I don’t understand that. The movement…

Steve Paxton The movement was subject to another process, which was being the servant to the typist, who was typing the tape. So the tape was actually running the situation. And, really, we both had a relationship to the tape machine.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s a great structural device, also. It's unpredictable, it can…it will structure your movement sequences. So, it’s like you find also a way to add or to have composition. Were you, other than what the tape offers time-wise and action-wise, were you aware of other compositional tools you could apply to the movement you were generating?

Steve Paxton Well, I was aware of the choices I had to generate. I had to generate choices of movement and space and maybe even in relationship to the audience, you know, like how I performed the thing. It's unfortunate that I don't have the text. I have no memory of what the text might have been. I wrote it. It was my text as I recall, and I recorded it. And maybe someday I’ll come up against it. I don't know, maybe someday I'll find it.

Myriam Van Imschoot Is there an audience member we could ask that you remember that…

Steve Paxton It might be possible to find the typist who typed the text. But I mean, I've been out of touch with this guy for…

Myriam Van Imschoot I can do that.

Steve Paxton Well, his name was Dwayne, and he was…he worked for Douglas Chrismas at the…at Douglas Chrismas’ gallery in Vancouver in 1967. And he…and Douglas Chrismas now has a gallery in New York City - the ACE gallery. So, it might just be possible to track this guy down, but if he would have any memory of this, I would be very surprised.

Myriam Van Imschoot Why would you be surprised? Just because…

Steve Paxton …because it's 35 years later, you know? Anyways, so that was '67, and it wasn't until the early 70s that I decided that I had had enough. I had been 10 years working with pedestrian movement, and I was ready to move on to something, and I decided that improvisation was… By that point, I was interested enough in this problem of defining it through action that I went on to - actually, I thought I would - well, another 10 years…the next 10 years, I'll devote to improvisation, but it has proven to be much longer than that.

Myriam Van Imschoot Did you perform this solo a couple of times?

Steve Paxton I started it in Vancouver, and I performed it all the way down to San Diego. So, it was Vancouver, Seattle, Portland, Oregon, Berkeley or San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego.

Myriam Van Imschoot That’s really important because for your question, defining that word, you need a couple of performances…

Steve Paxton You definitely need more than one. [laughing]

Myriam Van Imschoot …at least!

Steve Paxton Maybe more than two. No, I performed it for a while, and I realized that I had a lot of limitations in terms of how I could improvise or what I thought it was, you know, so… And I began to realize that I was defining it…that nobody else could define it for me. And that, I think, is important to realize about improvisation. I mean, people who teach improvisation, myself included, I have heard say that it can be learned, but it's not possible to teach it. But you can help people. You can put them in a position where they can learn it. You can help them learn it by first of all, just by using the word and suggesting that they try.

I was brought in as a lecturer to Bennington College at some point in the 80s…the point at which I did Flat, so whatever date that was. And I was shown a class of people who are studying improvisation with a number of people…Dana Reitz and myself and other people. And I was one of the sort of late…I was late in the series. So, I came in, and the dancers were warming up, and I said, “Have you, have you warmed up?” and I got some responses. “Yes, you know, we’re warming up.” And I said, I can't remember exactly how I said it. But I asked them if they were ready to improvise. And they said yes. And so I said, “Well do it,” [laughing] and they did! That's how we started. And so, I made them define it for me. And then afterwards, we talked a little bit about what they had done, but not on a level of good or bad or anything like that, but just what actually occurred and what choices did you make and or did you do this or what happened there that was interesting to me, you know, sort of dealing with it as phenomena, and I think it is phenomena, and whether it is art or whether it is even performance in the normal way, I think remains to be questioned, but that it is a phenomena that you can do and play with and get material from is quite established.

Myriam Van Imschoot It seems to me that the solo was also a way back into dance.

Steve Paxton Well, the basic question of somebody who comes out of a strict training, and then you've got all this training, but, in fact, in modern dance there is this…the highest level of modern dance seems to be the people who did not do what their teachers taught them. So that you…if you look from Isadora Duncan, say, through Ruth St. Denis to Graham to Cunningham to the Judson students of Cunningham, you see that none of those figures followed their leaders, and that they took the permission to create a new direction when they became…once they left their teachers. So that's one level of work that the modern arts have, as opposed to people who sort of maintain the technique of their teachers as their work, which is another and very important aspect of things.

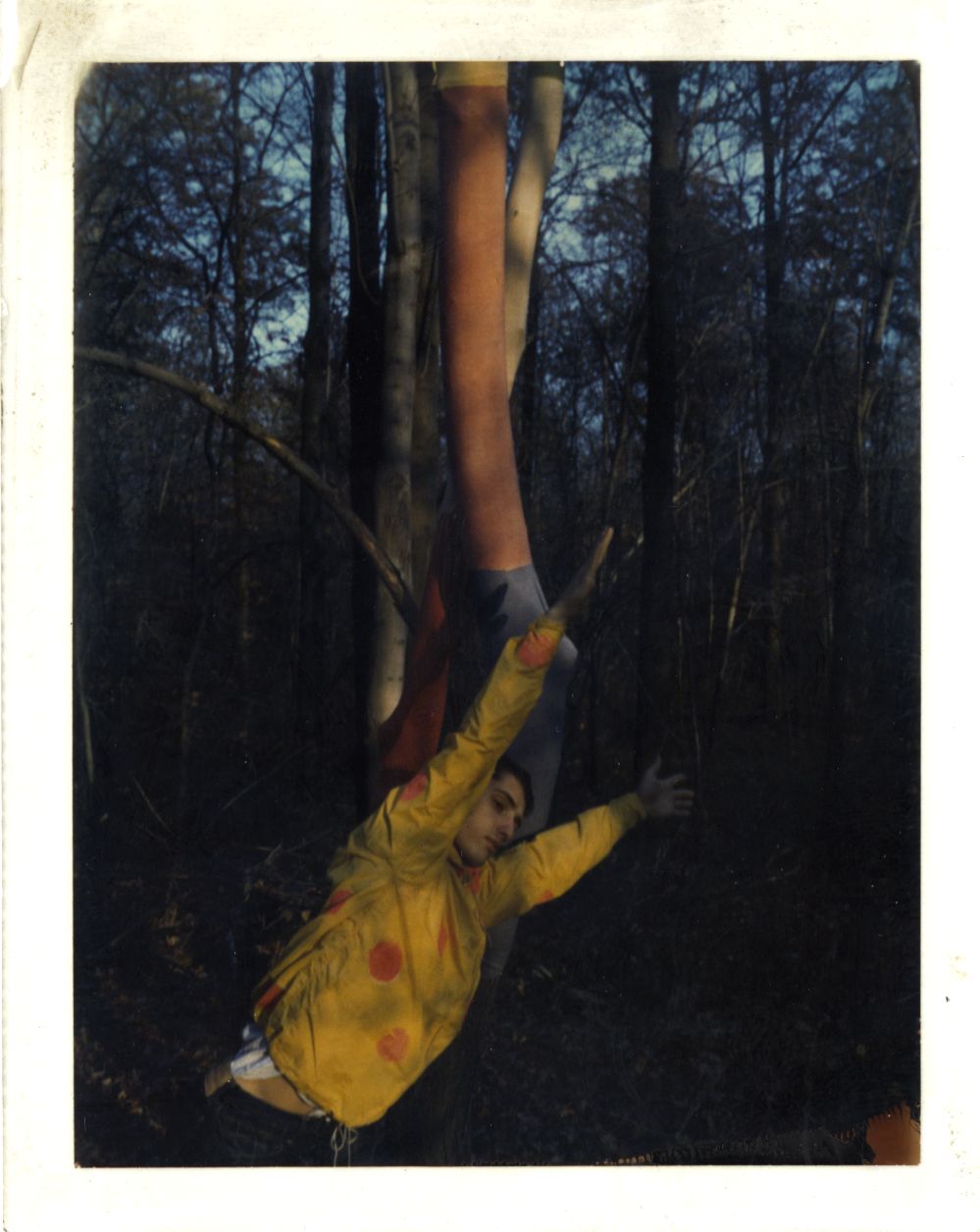

Steve Paxton’s Afternoon (a forest concert) (1963), performed in the woods near Billy Klüver’s house, Berkeley Heights, New Jersey, October 6, 1963. Photograph Collection. Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Archives, New York. Photo: Unattributed, 1963.

Myriam Van Imschoot Because if you look at that period of work up to '67, you can see that you were either on a pedestrian track, which is, of course, movement oriented, but it's not dealing with movement invention as such.

Steve Paxton Right, right.

Myriam Van Imschoot And then if it really was dancing or moving, like An Afternoon, it would be very much Cunningham-based.

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot Probably.

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot A lot of your works were bypassing the question of what to dance, in terms of movement invention.

The dictate of choreography16:09

Steve Paxton Not really bypassing it. I mean, what I was trying to do had to do with feeling that there was a real stricture, you know, a real constriction of possibilities by the dictatorship of the choreographer. And this went deeper than just the movement given. Dance technique, and subsequent choreographic use of those dancers who have been technically trained is a kind of brainwashing of the dancer into being able to accept motivation from another person for their movement, for the use of their body. It is a…it's something we clearly know I mean, war, you know, basic training kind of thing takes about six weeks to eight weeks to train people to, you know…

Myriam Van Imschoot Kill?

Steve Paxton …go from being students and accountants and storekeepers into killing machines, and so it doesn't…brainwashing is not unusual, but it was unusual to think or to realize that I had been through such a process quite willingly. I enjoyed the whole thing of giving my body over to somebody that I thought was a great choreographer, but then realizing that it makes certain things happen, like, I didn't know what I danced like. I knew what I danced like in the style of my teachers, but I didn't know what I had to give. So, that question you could say I was skirting is…that's a question you said I was getting around, but, in fact it's a quite normal process to go through that. And the idea of choreographing in the style of Cunningham or Graham or Limón, three very influential teachers for me or in ballet, you know, which I felt unprepared to even do technically, somehow seemed a kind of degradation of the work that they had passed on. That the real work that they had passed on was that you could create a movement style or technique, a new process, a new way of looking at the body, and that that was the, finally, the most precious gift that they had given. The repertory was proof and presentation of that movement work, but that it was important to create a vocabulary. It was important…like writers, you know, to find a voice within the body. So, I felt that that was my basic job, to discover what my own voice was, but there's no way that somebody can do that for you, you know, you actually have to grasp yourself by your own horns [laughing] and wrestle yourself around and find out what you want to do. So, it's a long processing of the question, what…how do I dance?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. Did the presence of the tape, like the tape recorder, did that evoke for you any kind of connotations as to a technology of reproduction versus the unique improvised solo or dancing, you were…

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot …you were aware of that opposition you were playing with?

Steve Paxton Yes, yes.

Myriam Van Imschoot Can you tell something about that? I mean, about that awareness or about that…

Steve Paxton I think you said it so well. [laughing]

Myriam Van Imschoot Saves time!

Steve Paxton Well, it was my voice being heard and my body being seen, and my voice was controlling my body.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton And my voice was not my voice, but it was mechanically reproduced, so it was actually the limitations of the tape machine controlling the situation.

[…]

Myriam Van Imschoot Do you have a feeling that this opposition was alive at that time? Like there's more and more available technology for reproduction, and something we could say…improvisation is something which is, well, challenges the idea of reproduction. Was that something alive in that time?

Steve Paxton I think it's obvious. You know, even at that time, we were hearing dead people sing all the time on the radio, and we still are and there's more and more of them. We have a huge repertoire of voices no longer connected to human beings. And it’s not been possible before this century. So, it's pretty obvious that it's happening, and that it's going to have an effect or has had an effect. I mean, every time I hear Janis Joplin, what am I supposed to think, you know? This is a reproduction being played into a broadcasting system and being reproduced on my radio. It's a completely mechanical event. It has absolutely no feeling…absolutely no…There's nothing human about it. It's the most abstract thing that's ever happened, and yet I hear Janis, you know, getting down again, and I'm filled with emotions. I find it so bizarre. I think we're in a very bizarre situation.

[…]

Robert Whitman, Two Holes of Water - 3, 1966. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot There's a lot of typewriters in 60s performances. It’s, you know, in the music of Cage. There’s a lot of them. In Claes Oldenburg’s Late Happenings, dealing with some secretarial women typewriting, Robert Whitman1 in his, in the Nine Evenings piece that he did, there was a typewriter. There seems to be somehow an attraction for avant-garde artists at that moment, and I was just wondering why. What that object represented at that moment because I have a computer. I am from a computer generation.

Steve Paxton But the typewriter was what we had. Yeah, I don't know what its fascination was. […]

Myriam Van Imschoot When you were saying that your dead voice, if we can call it that way, was dictating your life presence because it really was kind of a…

Steve Paxton Controlling.

Myriam Van Imschoot Controlling. Does that imply critique on the technological tool you’re staging, you’re using, the technology it represents?

Steve Paxton A critique, maybe an observation.

Myriam Van Imschoot An observation.

Steve Paxton And also, I mean, there are three relationships: there’s the tape machine to the audience, there’s the tape machine to the typist, there’s the tape machine to the dancer, and as the dancer was also the voice on the tape machine, I was apparently…

Myriam Van Imschoot Split?

Steve Paxton I was, well, not split. I was doubled. Different than split. I was providing one line of thinking through the machine, and I was then free to have a completely different line of thinking in my dancing and to work in on different levels, so…

Myriam Van Imschoot Did you magnify the sound of the typewriter or the tape recorder?

Steve Paxton No, no.

Myriam Van Imschoot Was it audible for your audience, then?

Steve Paxton Yes, it was audible and visible, and it was clear what the job was.

[•••]

Myriam Van Imschoot So, what else was on the program? [•••]

Steve Paxton Oh, Satisfying Lover, State, Salt Lake City Deaths… And this…it might have been Audience Performance #1. I really can't remember the name of it. But there was something in…the Audience Performances were events in which…Audience Performance #1, as I recall, was somewhat guided, but it left the audience a chance to do more or less what they want. It's sort of another word for intermission, as well, an audience performance. Audience Performance #2 was completely open as to what the audience did, and sometimes, people would get up and dance or run around or…

[•••]

Myriam Van Imschoot Tell me something more about the audience…

Steve Paxton …performances?

Myriam Van Imschoot …performances. Yeah. I’m really interested.

Steve Paxton Well, I mean, I can't quite remember them. I just remember that they were a situation in which the performance power was shifted from me to the people watching me. The right, the permission, the whatever.

Myriam Van Imschoot Was the tour the first time you…

Steve Paxton I wonder if Audience Performance #1 was…there was an event at The New School in which I gave the audience cards with lines on them, and each person's activity or line - stand up in the audience, and say their line - triggered, in a kind of like lineage way other events in different parts of the audience. So, that might have been Audience Performance #1, the cards and the readings, and then audience performance…that's probably…that was probably right.

Myriam Van Imschoot That’s very…the New York performance was right before you went on tour?

Steve Paxton In '67?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. So, you went on tour, like the New York performance was in November or something…

Steve Paxton That was The New School performance, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot So you left in the winter for…

Steve Paxton My first solo tour!

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah! Late '67 up to '68, your tour, and you did some more audience performances.

Steve Paxton Yes, I did these performances.

Myriam Van Imschoot How many performance events did you make?

Steve Paxton The '67 tour was a Spring tour, so I started in Vancouver and went to San Diego. In '68, I did it again. I did it for about eight years, that tour at that same time.

Myriam Van Imschoot There's fairly few or little information about those performances.

Steve Paxton Well, I do have some people I could ask if they remember anything. And the other thing is one of them was at Mills College, so Mills College might have some record or memory.

Myriam Van Imschoot I’d love to do that, actually yeah.

Steve Paxton I did another one at ACE…Oh! I had a couple of other pieces. There was Beautiful Lecture, which was the contrasting of a pornographic film with Swan Lake with myself in the space between. What else did I…there was something, I can’t even remember, called A Lecture on Performance. I wonder if that was the one with a dog with like a…

Myriam Van Imschoot If you like, we can go into that in questionnaires because that would mean that I put out all my little bits and pieces of what I found…

Steve Paxton Of information to spark my memory…

Myriam Van Imschoot Of information, and then, you can see more.

Steve Paxton Well, it would be good to get everything tied down properly, so I don't misattribute.

Dunn's workshop and Trisha Brown29:17

Myriam Van Imschoot [•••] I jump to Robert Dunn’s workshop. According to Trisha Brown, who was involved in improvisational dance from early 60s on, she's like, really pursuing that track. At the time, she said that although it had some role in a workshop, as it will have in any kind of workshop dealing with creation and process and all of that, she didn't feel like it was like highly valued for one thing. And that secondly…

Steve Paxton Not only not highly valued, I mean, maybe not valued because not understood, and not present. That is, there weren’t examples of improvisers in New York that I know of, so it was rare.

Myriam Van Imschoot The second thing she said [•••] when she did it, she felt also that there was…that it was ambivalent…

Steve Paxton The response?

Myriam Van Imschoot The response. That people felt uneasy about some virtuosic display that was part of the physical feats that she was into while doing these improvisations. So that there was a slight…not only disinterest but maybe a slight disapproval of this artistic stance or…

Steve Paxton Well, I certainly couldn't feel that.

Myriam Van Imschoot No, that's right.

Steve Paxton And I didn't pick that up. I wonder if that's not a bit of kind of paranoia on her part because I think the real problem is that we had absolutely no way to mentally grapple with what she was doing. She was doing something that was obviously different than composition, and the way that we were attacking it and the examples that we had, you know, Cage scores or even going back to an earlier age, the Louis Horst…essentially use of music as a format. So here was something without music that was just emanating from the body that this person was evidently able to do in the way that a jazz performer can blow, you know, and there, the rest of us were drawing a blank about what was this space, which is a great place to start, but we didn’t know that. We just thought we didn't understand it. And we didn't know what she was suggesting by doing it, you know. Were we to learn this? Were we supposed to be able to do this too? How was it that she had permission to do this, and we had never been told to do it, you know? Yeah, it was, it was a permission that had arisen, I guess, with her work with Anne Halprin and with those artists on the West Coast, and most of us had not any experience of what she had found. So, she can say it was undervalued or whatever, but I don't think it was a question of that. And you find a new stone or a new artifact of some sort, you don't know what it is unless you can see it or find it in its site. It's like an archaeological process in the arts. She found it someplace where it had value, where it was understood, and somebody like Anne who knew how to work with it, or Anna as she’s now known, knew how to work with it or to suggest it, or knew why to value it. Cunningham I'm sure considered improvisation just one starting point that was known for making dance, and he had found others. He didn't…so it just wasn't very present. Now, it may have been happening. I mean, there were still Isadora Duncan people in those days, sort of the late 50s.

Myriam Van Imschoot Like teachers and schools?

Steve Paxton Well, practitioners, you know, going into studios and wafting around with veils and expressing themselves in the way that the Duncan thinking had been. I think it's slightly degraded. I mean, Duncan herself, claims not to have been an improviser, but these people were clearly not following any particular program. I used to watch them through the cracks in the studio door, you know, when they were in there prior to my class. And it gave improvisation the name of something practiced by women in their 60s who were dressed a little bit inappropriately and revealingly, you know, and with a lot of veils, like a kind of Salome’s dance of seduction, and intrigue and all that business done by you know…

Myriam Van Imschoot Free, expressive dancing…

Steve Paxton Free, expressive dancing. Whatever, you know, all these things we try to say about it, which actually means not very much expression, not a very big range of expression, not a very big range of possibilities. Yeah, just the barest nibble of what I think improvisation can be. And I thank God at least somebody was doing something that was not rigorously…or aesthetically rigorous to point out that not all movement need have that quality.

Myriam Van Imschoot […] I think it's also the remark of a sensitive artist, you know, who also must have been unsure, you know, the whole question of response and how people value one’s work is always…

Steve Paxton Yes.

Myriam Van Imschoot …interspersed with anxiety. I’m sure you can…

Steve Paxton I could tell you stories of my own paranoia. I mean, I'm not…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, tell me.

Steve Paxton Why?

Myriam Van Imschoot I don’t know.

Steve Paxton It’s not so interesting. It's just that one is in a position of being evaluated from outside. Now, what is paranoia except feeling that outside you there is some danger, you know, that they're out to get you? Well, they are out to get you if you're a young artist. In a way, they're out to evaluate you. They’re out to look at you as nobody is ever looked at in this culture. There is no…well, sports figures, perhaps, you know, but presumably, they're on a team and it's, you know…boxers perhaps or tennis players get this kind of scrutiny of every move and every…and if you're doing something, which doesn't score points, that is to say, if there's no way really to evaluate whether Trisha Brown is scoring at this moment or is losing at this moment, you don't know what is going on, then you are in a different aesthetic realm entirely than the kind of security that more formal artistic stuff presents.

Myriam Van Imschoot […] It's the difference between saying, like, I felt undervalued and saying improvisation was undervalued.

Steve Paxton See, she knew something.

Myriam Van Imschoot I’m sorry?

Steve Paxton She knew something, or she felt something about improvisation, and it's…

Myriam Van Imschoot You didn’t feel like that was shared, a shared interest?

Steve Paxton But it turned out, actually, I mean, her presentation of improvisations was one of…and her focus on improvisation and Simone and a few other people in that crowd.

Myriam Van Imschoot Who were the other people?

Steve Paxton Who would improvise? I think Yvonne improvised to some degree or would claim to be improvising, you know, as opposed to…but Yvonne was actually more formalist in general. No, a few people kept that torch, you know, those embers burning through the years, and it finally was what provoked my questioning of… “Oh, what do they mean? What are they doing?” You know, when we work with a score, we know what we're doing. We know something about the process that we're in. How can you just suddenly depend on the whole human temperament, armament, and aesthetic choice-making mechanism in the instant? How can you go into the instant? And it tallied, for me, along with the mysticism that was being discussed by John Cage, you know, with his studies with Suzuki, with the Beats, and with my own kind of limited understanding of the Stoics, that there was another way to view time. I guess I was beginning to understand that what you think, what paradigm you hold, determines what you do, and so I was saying, well, what is this paradigm where there is no named paradigm? What is it when you go outside of definition? And realizing that I hadn't been outside my own self-definition or somebody’s definition of me, you know, like I…which is all a very tricky world anyway, I mean, that, you know, just the simple…

Myriam Van Imschoot The decision to go outside.

Steve Paxton …the simple…to go outside is already a journey.

Yvonne Rainer and improvisation39:05

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, just to parallel Trisha Brown’s remark with another remark that has some similar…has a similar ring is Yvonne Rainer about her improvisations, and she did improvise. I mean, although she indeed was more of a formalist, and she stresses the formalist side of her. Even in retrospect, when I came…when I went to her to talk to her, she would kind of say: “Well, I've never really improvised [laughing]. I didn't do that, but, you know, I'm not the improviser. other people are. You know, ask Steve. You know, I don’t know.”

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot But that’s in hindsight, with an insight that she…you know, when people really pursued that track from that point of view, indeed, she isn't an improviser. But if you would think of her as she was in 1965, like I have no idea what's going to happen, then she's like…she’s one of the persons who actually is trying things out improvisationally and has some improvisation solos even and duets and so on, so I didn’t really buy her…

Steve Paxton Her putting it aside?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton I think she likes rigor.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton And, with improvisation, you have to accept a period before rigor reappears, and it can be quite a long period, you know, of a lack of substance in the work that you can think about, that it takes a long time for consciousness to seemingly go from rigorous technical or structural making of dance, and into an area where you don't have those props anymore. And where you have to make…you have to choose from a much vaster realm of possibilities than the structural way provides.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, she has these polarities in her anyway to…I think maybe people forgot about this crazy woman that's in her, some of the quirky movements and faces, you know…

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot Facial expressions she used to have, some really like…characters reappearing in her dance style, which she at a certain moment really dismissed saying, I don't want to act…do this lunatic woman act anymore, and she associates that somehow with improvisation too. And it also seems that Robert Morris was a little bit influential in that, too.

Steve Paxton We're talking about the period of the manifesto?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah and so he disliked that aspect very, very much.

Steve Paxton Have you talked to him?

Myriam Van Imschoot I would, I plan to, if ever, you know, someone can…

Steve Paxton He's a really nice guy. You'll have a good time with him.

Myriam Van Imschoot So, I would be very curious to know because he had an Anna Halprin background, so he knew. I mean, he wasn't ignorant of…

Steve Paxton I didn't realize that. I didn't realize he had an Anna Halprin background as well.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, he tried some classes, and he was around, so he…

Steve Paxton …and he was connected to Simone.

Myriam Van Imschoot He was so…in that period, he was doing abstract expressionist paintings, and she was doing abstract expressionist dancing. So, it’s rooted, but, yeah, so the dismissal of a certain part of Yvonne Rainer’s being or work or whatever was also somehow a little bit keeping improvisation at a bay. Not thinking that was maybe the right…

Steve Paxton Artistic direction for her…

Myriam Van Imschoot …artistic direction, yeah. So it seems like I have two remarks. One of Trisha Brown saying I was doing it, but it wasn't really liked, and it's Yvonne Rainer who has this in her work, but from herself and other people…

Steve Paxton She didn’t value it. Maybe the two remarks really go together hand in hand. There was Yvonne dismissing it, and there was Trisha saying it was undervalued, and they’re friends at that time, right? They're still friends, but I mean, they were friends at that time, so maybe that was where Trisha’s perception of what was going on came from.

Myriam Van Imschoot But was it at a certain point maybe, felt that it was just too hot a form in a cool era?

Steve Paxton Possibly, but I mean, you're asking me, you're asking me to make a judgment about a whole group of people and their assessment of this work, you know, and I mean, what was happening at that time basically was the assault of chance procedures on non-chance procedures, so-called non-chance procedures, which actually arise from improvisational procedures, the non-chance, you know, instinctual movement production of which goes into choreography and set material and repertory and the foundations of dance culture in a way. You know, the pillars of our…but yeah, there is this other thing, which is…has always been there, and which obviously choreographers use to some degree to make material.

Myriam Van Imschoot Always, yeah.

Steve Paxton So…but it wasn't a performance form. So, Trisha was saying it was a performance form. She was one of the few voices along with Simone and Yvonne to say that, and she continued to want to say that…and she was one of the instigators of Grand Union in that way because she told me that the point was…could we young choreographers get a grant to, you know, get the National Endowment for the Arts, for instance, to acknowledge that we were improvisers, and this was an art form? Could we get it acknowledged? She had a program.

Myriam Van Imschoot She had a mission.

Steve Paxton She had a mission, yeah…

Myriam Van Imschoot On the other hand…

Steve Paxton …and they didn’t.

Myriam Van Imschoot They didn’t!

Steve Paxton We got some grants from them, but it was always under the pretext that one of us was choreographing the Grand Union, you know, which never happened.

Myriam Van Imschoot Interesting.

Steve Paxton So, we all lied to each other, you know, in a socially acceptable way to get this money. I mean, we lied to the NEA, and the NEA lied to us, for instance.

Myriam Van Imschoot Consensual lying.

Steve Paxton Yeah, they had to give money under their mandate, which didn't include the word improvisation. We were trying to get them to change their mandate just a little bit to see what would happen.

Myriam Van Imschoot And that didn’t happen?

Steve Paxton Mhm. [No.]

[…]

Steve Paxton It's still an issue, and I think it's a very, very potent issue because I don't actually, at this point, understand how you give a grant for something which is essentially free and open, to manifest in the same way. You can more conventionally give grants for the process of making choreography and training people. I have to say that for my Guggenheim, I wrote and I told them that what I was going to do was train people to work in a technique. That was what I proposed to them. When it came out in the program, you know, when it was published, for all to see that I'd gotten a grant, it was a choreography. So, I mean, they're stuck on certain words, and these words are…

[…]

Steve Paxton They need the words. They need help. They need conceptual help.

[…]

Myriam Van Imschoot Going back to say the Judson era. First of all, the first concert, in its program, its announcement, foregrounds compositional methods. It's something rare. So at that point, if you announce an event that you kind of forward the compositional tools you've been working on…as you mentioned, there's chance or rule games or…improvisation was within a list of that, so it’s mentioned. It’s there. The second concert, the one in Woodstock, not everyone was in that because its summer, and people are…but there's a second concert, and that has even a note on improvisation. I can maybe read it later. This third and fourth concert, about those concerts Jill Johnston writes that they were decisive in moving a little bit away from the Cagean and Cunningham model that had been so prominent in the workshop anyway and also away from the chance, the central position that the chance method had, and she mentions two examples where she sees that it moves away from the chance, and she mentions repetition and improvisation. So, already, we're in the early concert history, we find every time a mentioning of improvisation, which is interesting, because you have on the one hand, people saying that it wasn't maybe that prominent, or we didn't really know what was going on. Some people are doing it, and yet, it’s clearly foregrounded in a public announcement in a program. So it's like it's present and it's not present, you know. It's there, and it's not fully there.

[…]

“Forti’s simply typed handbill for her performance event titled “Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things, by Simone Morris,” listed Ruth Allphon, Carl Lehmann-Haupt, Marnie Mahaffay, Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, and herself as participants, along with a “tape by La Monte Young.” Forti’s works were performed twice, on Friday, May 26, 1961, and on Saturday, the 27th. Her event was one of a series organized by Young, with Yoko Ono, in Ono’s loft space at 112 Chambers Street in downtown Manhattan. Ono intended to make her loft a performance space that was an “alternative to classic concert halls uptown,” according to Midori Yoshimoto. One of several similar events during 1960 and 1961, the Chambers Street series represented an early bringing-together of experimental music and other performance practice that shared in common a concern with the score after Cage, a pared-down approach, and an emphasis on the single “event.”” Meredith Morse, Soft is Fast: Simone Forti in the 1960s and after, The MIT Press, 2016, 84-85. ↩

Steve Paxton It was there in a very new state. I mean, it was not what I would call highly sophisticated improvisation by our standards today. In other words, things have moved on. We now see improvisation a little bit more objectively. At that time, it was incredibly subjective as opposed to the other methods we were using. And very difficult to talk about. There was no vocabulary. There weren't examples. There weren't…this was prior to contact improvisation, which was, as far as I know, the first time there was a named methodology beyond just the word improvisation. It…Simone didn't use the word improvisation in her Dance Constructions2, and yet, they were, you know…by today's standards, clearly, ideas within which one improvised a form, but it was a discrete form that one was improvising within. A little bit as though you would improvise the blues or improvise cool jazz or something. So, we were just arriving at that state. Simone would probably be really the person who first put forward discrete forms of that kind of work. Whereas Trisha’s improvisation or Yvonne’s improvisations seem not to be discreet forms. They seem to be unformed, and that was their claim to improvisation, you know, the sense of lack of form although you had a resultant form in that you look at a performance of something, you know. You could say afterwards what the form was, but you couldn't, nor could they probably, have said what the materials or the space or the performance quality would have been ahead of time - nor would they repeat it, you know. I don't recall, for instance, that their dance on the chicken coop roof at Seagull’s Farm, for instance…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, I’ve seen a film, actually.

Steve Paxton I don’t think they…I don't think they repeated it. I don't think they tried to say, “We're going to do again what we did out there,” you know, kind of thing. Whereas Simone repeated…

Myriam Van Imschoot Her Constructions.

Steve Paxton The Constructions.

Simone Forti. See Saw from Dance Constructions. 1960. Performance with plywood seesaw. Duration variable. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Performed by Simone Forti and Steve Paxton at Galleria L'Attico, Rome, 1969. Image: © 2020 Claudio Abate, courtesy of Simone Forti and The Box, LA.

Myriam Van Imschoot What about…if people mentioned like two major influences on the work of those young people in the workshops and even out of the workshop context? It's Merce Cunningham and John Cage you just mentioned, and then these other lineages, the Anna Halprin lineage. So, if that’s true in terms of lineages, running through the memetic pool of the early 60s, how would you have assessed this Anna Halprin lineage? How would it have appeared to you or become visible to you?

Steve Paxton It would have been the unconscious as opposed to the highly conscious. It would have been like a model of the brain, you know?

Myriam Van Imschoot Because sometimes, I think it’s…there’s like a risk of making something nearly schematic. There's like the Cunningham and the Anna Halprin, so you have a father, you have a mother…

Steve Paxton Oh dear.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s Apollonian versus Dionysian. It’s Urban versus Nature.

Steve Paxton Yes, yes, go on…

Myriam Van Imschoot And since…

Steve Paxton But why versus? Why not complimentary?

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, yeah, you can say it compliments. It's…

Steve Paxton I mean, if we had open minds enough to try to work with new structures and try to understand how new structures would impact on the dance forms, why wouldn't we have been interested in all the new…all the possible structures? I mean, we were, and yeah, I feel like Trisha’s remark that it wasn't valued…I mean, aside from agreeing that we didn't know how to value it and therefore it was difficult to…

Myriam Van Imschoot …assess.

Steve Paxton …assess or say anything about at all, I don't feel like it was not influential. I feel like it was influential and existed there as a very potent force. Especially in contrast to the more intellectual approaches that we were mostly involved with. But I mean, for instance, in my work, I tried to get away from both the intellectual approaches that we were involved with and this other force that seemed to be coming via Trisha, Yvonne, and Simone, and a few other people, Ruth Emerson, I remember, also was an Anna Halprin person. So, they had a kind of understanding of something that the rest of us were only just getting a glance at, you know, a glimmer of, and…so, anyway, I tried to stay away from that too. I tried to find my own voice, my own way of making some kind of creation.

Myriam Van Imschoot Very often when there is like…there have been like major, more improvisational events in the concert series like Charles Ross, who provides an environment for improvisational activities to happen, and there's some other examples, but very often, I don't find you back in particularly those concerts.

Steve Paxton I happened not to be in town. Don’t forget I had to also…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, you had quite a life!

Steve Paxton Yeah, I was touring, also. So, yeah, maybe everything would have happened much faster had I been able to be there for that.

Myriam Van Imschoot You are mentioned improvising a rule game with…I'll look it up…the over/under/around rule game?

Steve Paxton Well, as I was in Simone’s Dance Constructions as well, so I was doing it but not necessarily. I mean, when you call it a rule game, and somehow you've evaded the word and the impact of…the void of the word improvisation.

Myriam Van Imschoot Well, a rule game is like a structured improvisation.

Steve Paxton Well, all games, actually, rely on improvisation, but again…I think that’s what rule game in dance acknowledges is that football, for instance, is an incredible improvisational setup, you know, as is tennis, and they're different. So, you have with every game. It's a place with rules within which you improvise. Or music. It's a place where there's some premise, that with which you're working. It’s very important. That premise gets all important, doesn't it, you know? What do you think it is? What is the paradigm for improvisation in this situation?

Myriam Van Imschoot If you were doing your own solo…did it seem that the Trisha Brown work or Simone Forti was providing you tools for your own improvisational solo?

Steve Paxton Well they were providing me with the questions. And I think what they did…I mean, I can't remember very clearly or, you know, or put this out as a certainty, but I think that what they did was much freer and much more like the improvisation of today than my work was. So, if they did provide some kind of pattern for me to work from, I wasn't very good at it.

Trillium is a three minute solo created and danced by Trisha Brown. It premiered at the Maidman Playhouse, New York, March 24 in 1962. “Trillium [is] a structured improvisation of very high energy movements involving a curious timing and with dumb silences like stopping dead in your tracks. I was working in a studio on a movement exploration that moved to or through the three positions of sitting, standing, and lying. I broke these actions down into their basic mechanical structure, finding the places of rest, power, momentum, and peculiarity. I went over and over the material, eventually accelerating and mixing it up to the degree that lying down was done in the air.” Trisha Brown in Hendel Teicher (ed.), Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001, The MIT Press, 2002. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot What I recognize as a nice kinship, is that the way the tape functions it goes against the grain a little bit of what you're doing, so it gives you…it gives resistance and even it sort of is a disturbing or unsettling factor. And it seems to me that Trisha Brown and her improvisations always have been looking for something that nearly like interlocks - No, how do you say that? - that short-circuits the two systems, like she would dance and talk because that was like something very hard to combine, so she would put her into a physical paradox where the systems, the two systems she brings into sort of give like an electric spark, you know, like…or even her physicality is very much about a physical paradox, you know, like if you walk up a facade or if you do Trillium3, and Trillium is defying nearly gravity laws or laws of physics.

Steve Paxton Actually, just laws of verticality that existed…

Myriam Van Imschoot Laws of verticality.

Steve Paxton …as a convention in dance.

Myriam Van Imschoot So she doesn't seem to employ improvisation to, you know, to go with it, but she uses always like something that will…that she has to fight against or that will…so, the tape recorder, those two elements seem to also have a similar effect or function. That's a strategy, I would say.

Steve Paxton It is a strategy. It’s a structural strategy. Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot So, it's interesting that that's…you didn't do an improvisational solo in which you were whatever for 12 minutes, but you were also looking for resistance and…

Steve Paxton …and structure and material. So, the structure and the material existed outside my body, and my body was doing whatever for brief periods of time.

Myriam Van Imschoot How did it develop from there on?

Steve Paxton I went on looking for other mechanisms. I mean, you know, having this structural background in dance composition. When I did the class at Oberlin College and realized that what I was working with had a structural integrity - Magnesium is what I'm talking about - I decided that structural integrity was structurally interesting enough to produce, you know, to go ahead and produce, to do a New York, you know, to perform in New York and to perform in New York at a very raw state, so that people would see the development of the form from it’s very first stages.

Myriam Van Imschoot How did the experience of being in Continuous Project - Altered Daily give also permissions for presenting something in a raw state or…

Steve Paxton Yvonne had several ways of…

Myriam Van Imschoot You were part of Continuous Project.

Steve Paxton I was.

Myriam Van Imschoot Very early.

The document Steve is referring to consists out of two subdocuments “Instructions for Steve and Barbara” and “Prescript for Steve and Barbara.” Both documents are to be found in Work 1961-73 by Yvonne Rainer. As Steve mentions, the letter indicates Rainer's willingness to “open up,” to let go of her desire for control and bring in new possibilities. Yvonne Rainer speaks of a “huge trust” in Barbara and Steve. She says: “Forgive me dear friends. As my affection and esteem for all of you grow I am forced to examine these vestiges of parsimony and control.*” ↩

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah, I was part of Continuous Project - Altered Daily, and I learned the materials and some of the materials were not set. I mean, for instance, learning something on stage, that there was material, so the dancer had to…was presented as a person learning dance in performance. And I just recall, there was a performance in the Midwest, and we were very high after the performances, and we would often talk for hours about what had happened, and you know, how the material had gone. And I said that it looked to me like we were headed for improvisation and that, you know, within a year, this would be an improvised performance. And Yvonne said no, and Douglas Dunn said he couldn't imagine how to improvise, and you know, everybody said no, essentially. And we were within a year doing the prototypical Grand Union if…I don't remember exactly the dates, but it might have been that we had changed to being Grand Union then. And that occurred, that change occurred because of Barbara Dilley and I being at the same time in Urbana, Illinois, and Yvonne was in New York and asked us to come and be in a performance, but we weren't going to be available for rehearsals of Continuous Project - Altered Daily, and she wrote us something 4 which suggested to me at least that we were free to bring new material.

-

Robert Whitman, Two Holes of Water - 3, 1966. ↩

-

“Forti’s simply typed handbill for her performance event titled “Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things, by Simone Morris,” listed Ruth Allphon, Carl Lehmann-Haupt, Marnie Mahaffay, Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, and herself as participants, along with a “tape by La Monte Young.” Forti’s works were performed twice, on Friday, May 26, 1961, and on Saturday, the 27th. Her event was one of a series organized by Young, with Yoko Ono, in Ono’s loft space at 112 Chambers Street in downtown Manhattan. Ono intended to make her loft a performance space that was an “alternative to classic concert halls uptown,” according to Midori Yoshimoto. One of several similar events during 1960 and 1961, the Chambers Street series represented an early bringing-together of experimental music and other performance practice that shared in common a concern with the score after Cage, a pared-down approach, and an emphasis on the single “event.”” Meredith Morse, Soft is Fast: Simone Forti in the 1960s and after, The MIT Press, 2016, 84-85. ↩

-

Trillium is a three minute solo created and danced by Trisha Brown. It premiered at the Maidman Playhouse, New York, March 24 in 1962. “Trillium [is] a structured improvisation of very high energy movements involving a curious timing and with dumb silences like stopping dead in your tracks. I was working in a studio on a movement exploration that moved to or through the three positions of sitting, standing, and lying. I broke these actions down into their basic mechanical structure, finding the places of rest, power, momentum, and peculiarity. I went over and over the material, eventually accelerating and mixing it up to the degree that lying down was done in the air.” Trisha Brown in Hendel Teicher (ed.), Trisha Brown: Dance and Art in Dialogue, 1961-2001, The MIT Press, 2002. ↩

-

The document Steve is referring to consists out of two subdocuments “Instructions for Steve and Barbara” and “Prescript for Steve and Barbara.” Both documents are to be found in Work 1961-73 by Yvonne Rainer. As Steve mentions, the letter indicates Rainer's willingness to “open up,” to let go of her desire for control and bring in new possibilities. Yvonne Rainer speaks of a “huge trust” in Barbara and Steve. She says: “Forgive me dear friends. As my affection and esteem for all of you grow I am forced to examine these vestiges of parsimony and control.*” ↩