1: Doubt, democracy, improvisation

Doubt00:00

Steve Paxton’s thoughts on the pressure and doubts when making “choreographic work” seem to come from a specific situation, although in retrospect it is unclear which. Was it the invitation to Mouvements (2003) at the Opera de Lyon, where Paxton would perform a duet with Trisha Brown called Constructing Milliseconds to music of Ammon Wolman in a program with work of Mathilde Monnier and William Forsythe for the Ballet d’Opéra. Or, was it an invitation to perform New Work at the Impulstanz Festival in Vienna (rather than proposing new choreography, Paxton invited The Lisbon Group for improvised group performances on 12, 14 and 15 July 2002)? Point is that Paxton can brood a long time over invitation before conjuring response. This interview cluster ends with an example of Ash, a piece that premiered in 1997 (deSingel, Antwerp) mixing in a then recent experience with his father’s death and the circumstances of his burial. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot Do1 you have the feeling of competing…that you have to compete with your past?

Steve Paxton Yes. And with the very highest aspect of it, which is, essentially, making new work. I think is…you know, all my heroes make new work, and the artists and my peers all make new work. So of course, I have to do it too. So much for being an avant-garde artist. I just happened to, you know, like that kind of work and wanted to participate. But it is…it's…it's, I think, the suffering…the six months of suffering is really an important aspect of it. The doubt and the fear and, you know, going up in flames right there in front of an audience. [laughing] Harsh reality.

Myriam Van Imschoot Do you have that feeling too there is more interest on the level of invitations or…

Steve Paxton Choreography. They want choreography. You know? What am I supposed to do? What is my choreography? I've spent my whole career trying to do something that wasn't normal choreography. They want pieces, but I think my work doesn't easily fit into another mind. I think my mind is the…it's…it's too complex to communicate. And I don't think language helps very much. And that's why rehearsals and said, there you are trying to rehearse with somebody, but you don't know what direction you want them to take. And in a way, I feel guilty about making them go through the doubt and fear that I'm going through, so I'm trying to be very stable for them, but I actually need to go through the agony. Well, I… It's not such agony, but it's just…oh, I don’t know…a little bit like your legs are too weak to move, you know. It isn’t agony, it's more doubt. So, then I'm in a position in a rehearsal of sort of having to pretend to be stronger than I am. And I'm not feeling like…I'm…I’m not right…in the right state of mind. So it's a complex thing.

The ethical problem of choreography02:24

Steve Paxton It's a political problem.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s a political problem.

Steve Paxton Or ethical problem. Yeah. Because how can you tell somebody else what to do if you don't like… […] How do you create a physical discipline? What choices do you use to make these choices, and rather new choices to be made beyond the ballet and modern dance, and other forms of dance['s] technical exercises? And so, the strategy seems to have been to try to create systems in which the people are…their choices are organized inside of certain parameters, but not…you know, for instance, space, or, for instance…or, for instance, the body, or…

Myriam Van Imschoot …vocabulary…

Steve Paxton …or some vocabulary, or, or, yeah, just creating vocabulary, or I mean any…any parameters would work as long as you aren't shown exactly what to do…as long as you have to make some choices to get there. Because it's very hard to overcome a natural human instinct to copy your or your other parental figures, your teachers, or your leaders in some way. And so, it's a question of how to get the copying to stop and the responsibility to start, and yet, still keep it organized enough so a discussion can be had around certain principles. Yeah, so it's a question of…yeah, so the technique has gone toward principles as opposed to exercises. And I am in that kind of system somehow. And it's still really new. If you can think of 30 or 40 years being new, but I mean, I think of…I think that the western dance is coming out from behind the skirts of the exercise mode, which is such a brainwashing when you get down to it, you know, it's five to ten years of intense brainwashing that you put yourself into that's called “learning,” that's called “being educated," but…

Myriam Van Imschoot …it’s disciplining.

Steve Paxton Discipline, etc. And, but what it does is…it…it takes you to a new place, but it doesn't let you acknowledge the old place. Yes, it makes you essentially choreographic material for a choreographer to use, but it doesn't teach you how to make your own decisions, or how to organize your ideas about dance in such a way that you're making choices that are organic to you. You're actually making choices then that are sort of… It’s sort of like joining chess, you know. Okay, now you can study all the strategies, and you learn all the strategies, and you figure out what all these geniuses have done before you and then you reproduce them. And it's in the brilliance of your reproduction that you're judged.

Myriam Van Imschoot And you try to outsmart them, but still, by applying them…

Steve Paxton If you can, if you can, you know, if you are one of those people that can figure out a new twist or a new wrinkle, that's the…that's the big prize. The thing is that we're then limited to what can be communicated. And that communication is mostly prescribed by language, and to some degree by example and to a large degree by the whole rote system of rehearsal and reproduction. Anyway, so it…it's no wonder there are so few choreographers, because we actually have a system that starts dancers off and almost erases their creative minds, or puts it aside for such a long period that by the time they come out of the technical work, all they can do is manipulate the technique with their minds. They don't… It would be difficult to maintain a sense of individual search, or…you would almost have to have that ego that show people are so famous for, or just be some kind of freak in a system like this to be able to be creative still at the end of the training. And [the] question is, is there perhaps another way, or is there perhaps another application, another level that should be pursued at the same time as the technique? Because I think that technique is important. There's a lot of information there. [There are] a lot of concepts in every dance class. And the idea of movement memory is not something that most of us employ beyond whatever movement memory we need for a job, you know, typing, you know, keyboard work, or whatever. Movement memory of the whole body is a pretty rare event. Not so rare as it used to be, though, because yoga and martial arts, and the dance techniques are all much stronger in the culture now than they ever were 100 or even 50 years ago.

Myriam Van Imschoot The choreographic tradition I grew up in, at the beginning of the '80s...what was very much at stake in those '80s choreographies was trying to develop a new movement language, or like a movement vocabulary if you want to say so. In the choreographic works from the '90s onwards, I see some kinda shift in interest that people think like, well, we have plenty of languages and let's use them and kind of look more at the choreographic framework or concepts that are, yeah, framework to pre-existing styles.

Steve Paxton So, it's all always reframing…

Between 1962 and 1964, a diverse group of choreographers, dancers, composers, musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists were gathering for a series of concerts at the Judson Memorial Church located at Washington Square Park, New York City. Although short-lived, this movement, called Judson Dance Theater, marked a radical reinvention of dance, choreography, and performance and has changed their history ever since. Although its style was varied and often eclectic, its main traits were an investigation into the movements of everyday life, undoing dance from its modern, theatrical, and structural conventions. Amongst its main participants were Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, David Gordon, and Deborah Hay. Of importance here is that the Judson Church Theater members would appear in each other’s works and thus nurture each other’s artistic practices. Such an unorthodox approach, which counteracted the way the modern masters usually would work with their dancers, led to the possibility to develop multifaceted embodiments and the versatility of lending one’s body to very different sorts of works, aesthetics, and signatures. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot …trying to develop the different compositional tools for making that framework actually. And whether your core that you try to frame is new language, or just conceptual questions, you try to highlight and use, you know, bodies for it. It’s very much…I mean, that's my tradition somehow in watching and having to learn to…to watch or relate to it. But, I mean, the thing I wanted to say is also that with this, this social system, that, you know, the ethics of working with people, and making something, whatever your intent or your ambition is, or your interest in research, I still don't understand why it's such a huge problem to you…because for example, the situation in which you were dancing in Trisha [Brown]’s work or being involved in Yvonne Rainer’s work or someone else's work…that would be like an alternating change of roles4, actually, because then you'd make a piece, and say I invite you, and it would alternate, so…

Non-hierarchical work10:02

Steve Paxton Maybe it's a more basic question.

Myriam Van Imschoot There was a capability at that moment to…

Steve Paxton Because I'm very happy in that role. Yeah, I'm very happy to play…to play somebody’s game and try to do it well. But in my life a more basic question came, which had to do with almost with politics, or almost with human…the necessities of human interactions, you know, what are the necessities of it? And I looked around, and I saw that I lived in something that was called a democracy. And what is a democracy? Everybody gets a voice. But in fact, I don't see democracy as being achieved in any very meaningful way. The voices of most people are…well, in America, for instance, once every four years, you get…

Myriam Van Imschoot …a voice.

Lincoln Kirstein (1907-96) was an influential American arts patron, writer, and curator, who dedicated his life to the modernization and institutionalization of American ballet. Together with George Balanchine (1904-83) he founded the New York City Ballet in 1946. He was also involved in the development of the School of American Ballet, which he led from 1940 till 1989. About the difference between a choreographer and a ballet master Kirstein writes in his book Movement and Metaphor from 1971 the following: “Let us distinguish here between choreographers and ballet masters. Such nomenclature is hardly binding; terms overlap, but a distinction between respective services can be almost precise. […] Choreographers put steps together from a syntax they receive; from this, they compose rather than invent dances. […] Choreographers are simple carpenters; ballet masters are cabinetmakers; some of them – the most gifted – sculptors. Ballet masters have the capacity to conceive unusual or novel movement beyond the range of the academy. Not only do they increase repertories with memorable work, but they also extend the academic idiom by new orientations and analyses.” Lincoln Kirstein, Movement and Metaphor: four centuries of ballet, Pitman, 1971, 16. For an analysis of the debate between the ballet-based norms of Lincoln Kirstein and the modern dance values, see the polemic between Lincoln Kirstein and critic John Martin in “Abstraction has many Faces: the Ballet/Modern Wars of Lincoln Kirstein and John Martin” by Mark Franko in Performance Research 3(2), 1998, 88-101. ↩

Steve Paxton …one tiny, little half hour of voice, you know, when you can make very major decisions. But the rest of the time, you're in a…in fact, a dictatorship, which you have elected perhaps, but it nonetheless becomes a kind of dictatorship. In a dance company, you're definitely in a dictatorship if you're in the usual model of dance company. I just thought: Whatever happened to the idea of…is it that democracy is too difficult to do? Is it that we can't do it, especially as a large group of individuals, that we can't allow individual voices or individual thought, therefore? And, of course, we're always encouraging people to find themselves and to speak up and to figure out what you want for yourself and ask for what you want. And I suppose we do it to some degree, but I think, by and large, the workable model is the military model, and… Have you read the works of or the thoughts of Lincoln Kirstein?5

Myriam Van Imschoot I’ve been reading especially his comments upon John Martin. You know, there was this correspondence between John Martin…

Steve Paxton John Martin, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot …John Martin and Kirstein that revealed a lot their positions, but I haven't actually read like entire books of him.

Steve Paxton Nor have I, but I've read things. Like, before he died, he wrote a couple of, you know, front arts page articles about the ballet versus the modern versus the postmodern.

Myriam Van Imschoot Those are the ones I would know.

Steve Paxton Oh, my God, he just saw no future at all for the postmodern because it didn't have a disciplined structure. A military school model is what he used to…and what I think everybody has used in the ballet. And the ballet actually does…the whole technical idea of [it] comes in a way from fencing. So it has a military background anyway.

Myriam Van Imschoot Base.

Steve Paxton Yeah, basis. And so I was just wondering, is this necessary? Do we have to have this, you know, and I was willing to try to not do that structure and try to find another structure. But it's hard to figure out. Who has the power? Who makes the decisions? Whose aesthetic reigns? Whose piece is it? All of these things in this new area, because in fact, it doesn't exist very much in the culture, so we don't have very many places where we have models to talk about the situations that we get into. I mean, we're trying to make work in a non-hierarchical way.

Myriam Van Imschoot When did that become an issue somehow to you, like…?

Steve Paxton Well, right at the beginning.

Myriam Van Imschoot Oh, right at the beginning?

The use of scores started as early as the beginning of the 1960s when Steve Paxton integrated elements that were picture-scored in the trio Proxy (1961) and the solo Flat (1964), both pieces created and presented in the frame of Judson Dance Theater. The photo sequences were to be interpreted by him or other performers and took the choreographer out of designing a dance and legitimized something that dancers do all the time, which is to give the choreographer movement suggestions. Photo scores were also used in Jag Vill Gärna Telefonera (1964), a duet with Robert Rauschenberg that premièred in Stockholm and later in the 1980s for the pieces Ave Nue (1985) and Audible Scenery (1986) with Extemporary Dance Theater, which shows that the interest in photo-generated movement resurfaced as a compositional tool and interest throughout his work. ↩

Steve Paxton I mean, in the '60s, I started making photo scores6 so I wouldn't have to demonstrate movement ideas. So there would be something to work from, that would be originated from me, but it wouldn't be a personal model. It would be a theoretical model. But it would still get us to places where we could make decisions, you know, like, if you make a photo score with a number of people, and there are photos in which both performers appear, then things have to be structured around that moment, so that they both appear in the same photo. Nevermind what kind of complexity they have to go through in their individual photo score up to that point. So, yeah, it was an issue for me right at the beginning. Is democracy possible? Or is it just a theory that, you know, like space, like zero, one of these gaping holes that we fall into, you know, we have a word that kind of patches bridges between the verb and the beginning of the sentence, you know.

Myriam Van Imschoot How would you see it idealistically, I mean, in terms of something to strive for?

Critical mass of improvisation15:06

Steve Paxton was a key player in the improvisation revival in Europe in the '90s. Especially the group improvisations marked the sign of the times as open events prone to experiment with other production and presentation formats. Honing unexpected encounters, these assemblies showed the larger need amongst a whole range of dancers, choreographers, musicians and artists to meet for exchange and collaborative synergies. This concurred with a new phase of internationalization, institutional growth of dance festivals, a stronger questioning of artist career as solidified on choreographic signature alone, and the tendency to look back to the legacies of the 1960s and 1970s in search of other information and models. Taking the participations of Steve Paxton as a lead, the weave of initiatives in Europe shows a broad range: he participated in the Improvisation Evening 1995 at Klapstuk in Leuven and the Night of Improvisation in Frascati Amsterdam in 1998, both events coordinated by Katie Duck. He was a guest at Crash Landing in Vienna 1997, curated by Meg Stuart, David Hernandez and Christine De Smedt, and again in the Festival On the Edge, curated by Mark Tompkins in three different cities, Paris, Strassbourg and Marseille. He danced upon invitation with Frans Poelstra as well as in the closing group improvisation event of Danças Na Cidade in 1999. It’s about the latter evening he speaks so fondly in this interview. The group improvisation in Portugal included Silvia Real, Teresa Prima, Vera Mantero, Boris Charmatz, Xavier Le Roy and Frans Poelstra, later referred to as The Lisbon Group. ↩

Steve Paxton Well, I have seen it, ideally. I have seen the ideal several times. In the current improvisational world, there are a number of people who have both the technical facility to create new movement modes easily to create intensely personal movement modes. You know, they’ve worked long enough that they’ve found something unique in their own way of moving, and [are] at the same time sensitive in space and one must almost say something like, well, socially, on stage with the other artists. And I think the models for it exist a lot in music and jazz and other places. Well, jazz isn't the only place where improvisation happens. But I mean, Bach was a great improviser. But where one kind of understands what kind of game the other person is playing and figures out what game. How one's own game can match, or if one should leave the stage, or if one should stop moving, or if one should join that game and drop this game because you're not working together? So, a couple of years ago, in Portugal2, there were a couple of performances just of the choreographers who had been in a festival. So, it wasn't really a group that had worked together at all. That was very ad hoc. But we did two performances, and each struck me as amazing in both the strength and the generosity of the participants. And what I see at a lesser level is that people haven't quite found enough of their own personal spatial orientation and movement orientation, so that they have to work very hard to produce this in the performance. And so they don't actually have the social or the interactive aspect of the thing, so they don't come to a kind of group image. So it is this question of how to be a group. Of course, we know that the military model achieves this, or having a big… Maybe if you all went on an adventure, you know, a couple of weeks in Africa together, by the end of that couple of weeks, you would, if you survived…

Myriam Van Imschoot You'd be much slimmer.

Steve Paxton You’d be much slimmer, and you’d be much darker. But, you might have achieved through the necessity, through the pressure, a sense of unity, you know, how each of you can contribute to the success of the whole endeavor. On a stage though you might only have 45 minutes to figure these kinds of things out. So, you actually have to be a pretty good player in order to do that in 45 minutes. So, I think you have to have played for a long time to have gotten to the point where you can play with any number and give everybody their space. You have to be…it's a…it's a mind that you’re building. It's a mental space that you have to work from in which your own production can be anything from minimal contribution to maximal contribution, but that's not the point. The point is, what does the contribution contribute to? So I've seen that happening, and I've seen it growing in the last 10 years, certainly the last five years, to an extraordinary degree.

Myriam Van Imschoot That's amazing.

Steve Paxton I mean, I think it is. I think we've finally hit critical mass with improvisation, where there are enough people dancing and enough people trying and enough people who've had, you know, been playing long enough that the issues are no longer “How do I survive this performance?” or “Is this okay?” or “I'm lost, what do I do?”, you know, into the next level, the next phase of it. And I think we're into the next phase, at least temporarily. I'm sure…I'm sure this is not eternal growth. I'm sure it goes up and down and in and out.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s conjunctural, probably. However, wouldn't people you've been improvising with before in group ensembles somehow feel disappointed in hearing that? Thinking that well, haven't we achieved that, you know, state of mind or that state of democracy earlier than in the '90s. And, you know, just…

Steve Paxton In performance, on stage, and in improvisations?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, just…

Sally Banes has described The Grand Union as follows:“The Grand Union was a collective of choreographer/performers who during the years 1970 to 1976 made group improvisations embracing dance, theatre and theatrics in an ongoing investigation into the nature of dance and performance. The Grand Union’s identity as a group had several sources: some of the nine who were its members at different points had known each other for as long as ten years when the group formed. They had seen and performed in each other’s work since the Judson Church days. Most had studied with Merce Cunningham, and three had danced in his company.” Sally Banes, “The Grand Union: The Presentation of Everyday Life as Dance” in Terpsichore in Sneakers, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980, 203. Amongst its members were Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Douglas Dunn, Barbara (Lloyd) Dilley, David Gordon and Becky Arnold. ↩

The Mind is a Muscle is an evening-length performance, which premiered at the Anderson Theater in New York City on April 11, 1968. It included some works which had been performed before, such as The Mind Is a Muscle, Part 1 (which would later get the title Trio A) at Judson Church in 1966. The piece comprised eight different parts and nine interludes, including dance sections danced in different constellations, her piece Trio A, conversations, songs, films, and a lecture by Rainer herself. Steve Paxton was part of the cast. In the statement on the program leaflet, Rainer writes: “It is my overall concern to reveal people as they are engaged in various kinds of activities – alone, with each other, with objects – and to weigh the quality of the human body toward that of objects and away from the super-stylization of the dancer. […] The condition for the making of my stuff lies in the continuation of my interest and energy. Just as ideological issues have no bearing on the nature of my work, neither does the tenor of current political and social conditions have any bearing on its execution. The world disintegrates around me. My connection to the world-in-crisis remains tenuous and remote. I can foresee a time when this remoteness must necessarily end, though I cannot foresee exactly when or how that relationship will change, or what circumstances will incite me to a different kind of action.” Yvonne Rainer, Work 1961-73, The Presses of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and New York University, 1974, 71. ↩

Steve Paxton Rarely. I mean, I went through five years with Grand Union7 and especially at the beginning, when it was a big adventure, and we were in Africa together, you know, I think we were…I think we've produced some amazingly generous performances in terms of the way we made the image, the proposition of the performance. But later on, when we had used up all our initial creative juices, and the real work had begun in fact, it got harder and harder to do. So, the question is a little bit how generous are you to the group, and how generous are you to yourself? And is there a way to achieve both at once? And I think the initial answer is no. I think initially, the answer, or at least at any one time, it's hard to be doing both. It is a mental space that you have to have created, and it takes time to create it. Or as Yvonne [Rainer] said, the mind is a muscle.8 That's…I'm not sure that's quite true. The mind is an organ, but she said the mind was a muscle. But what that leads us to think is that the mind, trained in various ways, will become stronger in those ways. And the way the mind is trained by the culture doesn't lead toward this kind of space that I'm talking about. Although, it's there, theoretically. It's there around Christmas time, you know, kind of thing. But is it…can you produce it when you're in that half-blind space of being a performer? Can you produce it when you're adrenalized and going through the stage shock as they call it of being in front of an audience? Can you keep all these things in mind under pressure, that kind of pressure? Can you do it even if you don't have organic trust or affection for your fellow performers? Can you make decisions above and beyond your personal self and their personal self into the overall identity of the work as it’s evolving? That's the question. And since it…the work can evolve in any, any way at all, what constitutes its nature? It's working with [a] huge amount of variables, and that's the space that is required to be comfortable.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, some people would object, saying that if it's more likely to happen now or in past five years, it's not because people have been more skillful. For example, in the groups you were mentioning, to some of the performers involved, it's still very fresh.

Paxton is referring here to the improvisation evening at Danças na Cidada, on 28 November 1999. ↩

Steve Paxton Some people were really struggling.3 […] I remember this one woman was really going through hell, and she was frozen. I mean, her body language just said: I'm scared, and I don't know what to do, and everybody else seems to and I'm outside. And it was a question that made me realize that she was inside, and she was noticed, and she was included in the image. I remember Vera Montero helped her for awhile, and I helped her for awhile, and sure, she helped herself for awhile, but in those moments, when you can see that somebody's lost or isolated, in the midst of it happening right in front of all the people and all that business, you know, you realize they're going through this weird catatonic moment, you know, on the question, just like, just like anybody else who’s got catatonia! How do you help them? What does create a situation in which they feel okay, and they can…

Myriam Van Imschoot How do you help without patronizing…

Steve Paxton Without patronizing! Or without taking over on any level? You know, once again, this question of the democracy of it: “Do you want to play? Can I, can I seduce you into playing? Can I invite you? Can I suggest? Can I leave a space that you will then use?"

Myriam Van Imschoot Or maybe just preparing conditions and…

Steve Paxton Preparing conditions. It requires all the subtlety of daycare. [laughing] With children, you know!

Myriam Van Imschoot Big Daddy!

Steve Paxton Well, not exactly. But understanding somebody, again, with this…this ability to step back from the…the frightened child, you know, and realize that maybe they just need their space. Maybe your contribution to them is to get out of their way, you know, and let them begin to work. You know, not focus on you. Yeah, I think we've probably discussed this in and out. The psychology and the physiology, and the training and the concepts all have to be there, and I think they are. At this moment, they seem to be available, and I'm seeing it. I'm very interested that I'm seeing it mostly in Europe and not so much in the United States.

Why Europe now?25:33

Myriam Van Imschoot Why is Europe…

American dance ideas and practices exercised a big influence on the European dance scene through various choreographers and improvisers teaching at the SNDO Amsterdam (from the '80s onwards) and EDDC Arnhem (from 1989 onwards). The development of somatic practices for performance, improvisation and choreographic strategies was amongst others disseminated by Eva Karczag, Jennifer Monson, Stephanie Skura and Mary Overlie. In the same line we could mention Dartington College, where Mary Fulkerson upon arrival in 1973 invited a line of American colleagues to teach with her. Contredanse was founded by Patricia Kuypers and had a pedagogical mission outside of regular art education that contributed to the dissemination in French artist circles. In 2009, Jeroen Fabius, currently artistic director of the DAS Choreography program in Amsterdam, published a book looking back on 30 years of dance education and development at SNDO, the School for New Dance Development, in Amsterdam. The publication includes contributions by Steve Paxton and Lisa Nelson. Jeroen Fabius (ed.), TALK/1982-2006, international theatre & film books, 2009. ↩

Steve Paxton Why Europe now? […] I think one must give a lot of credit to the Amsterdam and Arnhem new dance schools for providing information…9

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton …to a big slice of the European cultures.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton And then, the people who criticize them, you know, and then, the students of the people who did the criticizing, you know, the establishment, the students in the establishment, who looked at the criticisms of their parental figures and rebelled against that, still taking quite a lot of the useful material from the technical work and the choreographic work that they were trained in but doubting that the criticisms of their elders… I think that's how it works, and I think that's why it's taken so long because how long has it been? It's been 25 years or something since the information started developing in Amsterdam and…

Myriam Van Imschoot …basically, all nearly Netherland-based, I mean…

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah, that spark of the '60s.

Myriam Van Imschoot That flame!

Steve Paxton That, yeah, which is now sort of dying out…there. But maybe that's an important aspect of it, maybe it's like the phoenix. The flame was hot in Amsterdam for awhile for a number, you know, really a very long time. It's now not so interesting to them, but in the meantime, the information has been assimilated all over Europe, and people are trying it. And some of those people are achieving “space”, which enables them to work in a very mature way in improvisation. So that the imagery comes flowing out, and it can go [in] any direction, any of the players can play whatever game is coming along, you know, or somehow fit in. It isn't a question that you have to make certain moves. It's a question that…it's a question of the timing and the communication of the actions and the sounds, how they interlace to create a continuum…what the nature of that continuum might be during performance. And yeah, that's a useful word maybe, because it suggests that what we're talking about is more the quality of the flow of the energies through the performance as opposed to any one particular kind of element. Any particular quality of movement or spatial design, none of that is quite as critical as the way it flows from one thing to another, the kind of energies where they pause like…like the rushing of water downhill, you know. It pauses, it flows, it rampages, it goes very slowly, all of these things, but the main thing is that the basic rule of gravity is water is very obedient to gravity. And we have to somehow be obedient to our sense of flow and to not be personally inhibited so that we stop the flow, dam the flow in ourselves, and that we can contribute to the flow of the whole unit. And at the same time, not…we can't go running uphill against the flow that's happening.

Myriam Van Imschoot Too much effort.

Steve Paxton Yeah. Oh god, language. [laughing] It's something like that. So I think that this, this space is now available, and I see it maybe three or four times a year in performances, and rest of the time I see performances where you don't see that, where there is no cohesion amongst the performers when it's a group improvisation. Group improvisation is just the most extraordinarily difficult thing to pin down.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s just a whole genre in itself.

Steve Paxton Yeah, it is a very complex situation and a very human situation and at the same time, when it works well, contributes, I think, to our hope that people can create the present in an entertaining, safe, adventurous, new way. But I don't think we get it very often. But I think we're getting more than we used to.

Myriam Van Imschoot What I like about what's going on in Europe right now is that whether it's the result of information converging in…in people — the information that you’ve been talking about — or whether it's plainly ignorance and a desire to know more about it, which is also…

Steve Paxton But you're going to have ignorance because you always have new people coming into the situation.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah, but there’s this huge sense of discovery and of excitement and there's a huge, you know, willing willingness…you can say that?…to, to address something and requestion and look at…

Steve Paxton But isn't that the nature of Europe right now? Isn’t that the nature, I mean, politically, the overview?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton It’s being redrawn. It’s being readdressed. Governments are falling and rising, and we're not doing it by means of war anymore.

Myriam Van Imschoot No.

Steve Paxton It just seems to be like attrition, like, Oh god, I'm really sick of dictatorship, so, let's have a democracy. Oh democracy’s over, let's go back to communism.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton You know, like, we have choices. I don't think we had choices before. So, anyway, that's the overview. So, why wouldn't it be reflected in the dance and the arts and everywhere else, you know, like, let's overthrow what we did yesterday, but we're not overthrowing you know, in a bloody way anymore. I was just trying… I mean, art is such a good example of that. Anyway, it's a fairly bloodless form of human effort.

The democracy thesis31:35

Cynthia J. Novack, Sharing the Dance: Contact Improvisation and American Culture, University of Wisconsin Press, 1990. ↩

Sally Banes, Democracy’s Body:Judson Dance Theatre 1962-1964, Duke University Press Books, 1983. ↩

Myriam Van Imschoot Talking still about democracy, because, I mean, the word pops up in titles of books too like Novack’s book10 had it somewhere, I think, in the subtitle, if I'm not mistaken, and then Sally Banes has this “democracy’s body”11. And what is very implicit in the subtext of those books and many other articles, is that democracy is a good soil, of course, for improvisation or improvisational work, and that since The States or since America has this unique link to democracy, that it, you know, it's the most natural thing that improvisation would become important in America. So, it's kind of that implicit subtext that…

Steve Paxton You are talking about…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes.

Steve Paxton …the writers.

Myriam Van Imschoot I'm talking about writers. Yeah.

Steve Paxton And you're talking about the writers.

Myriam Van Imschoot So then it's like this huge sense of Americanness that's being situated in the form of improvisation.

Steve Paxton No.

Myriam Van Imschoot And the political system behind is a system of democracy and…

Steve Paxton I really disagree with that. I really disagree with that assumption.

Myriam Van Imschoot I wanted to ask that because of that. I know you have also a lot of criticism on Sally Banes.

Steve Paxton A lot of appreciation, but a little bit of major criticism.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton But I mean…

Myriam Van Imschoot …which still I mean for her, the democracy is also an important notion as it is for you.

Steve Paxton Well, she tends to make these giant assumptions. Like she was the one who foisted “postmodernism”…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton …on a whole generation of dancers, you know, which we can't seem to get rid of. It's like a glue that stuck to us, and, you know,…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. Yes. It’s mad and there’s always…

Steve Paxton …we are not allowed to title ourselves however we want. Sally Banes’s title has stuck to us, and it's not terribly accurate, you know. I don't think. But I mean, so yes, I could argue this, and I'm sure Sally would argue with her younger self, as well, because times have gone by and god knows.

Myriam Van Imschoot But do you really think that the importance you attach to democracy is so different as the one that Sally Banes attaches to it? I mean, there's this… What's similar is just the recognition of that being a very important component and element, and that's why it's so much part of American culture. I mean, that's the assumption, isn't it?

Steve Paxton I don't assume that.

Myriam Van Imschoot Okay.

Steve Paxton Democracy is not well understood.

Myriam Van Imschoot In America.

Steve Paxton By me! By me in America. [laughing] It's not well understood, because it's, in… As I understand it, it would require every person to be responsible for an overall image. So, I think it may be much more possible for a small group of people on stage than it is for a nation in which we urge every citizen to get out and vote and quite a few of those citizens don't have any idea of what's going on. As, in fact, probably 95% of those citizens, only half of the ones who do pay attention, all have different points of view, which I guess is supposed to be the strength of it. But there are certainly vast areas that every citizen is ignorant of. So in a way, it's ignorance voting, and that's a frightening idea. You know, wouldn't you rather have some very well educated king managing everything, you know, a good manager?

Myriam Van Imschoot That's our dream, isn’t it?

Steve Paxton It's our dream, the benign monarch or the benevolent dictator.

Myriam Van Imschoot The enlightened!

Steve Paxton Yeah, enlightened. So who's enlightened? I mean, we use this word as though we knew what it meant, even, you know, but unless you're enlightened, you wouldn’t have any idea! So, I think it's very complex. So, I think once again, she's hit upon an important concept, but I wonder just exactly what she means by it or what she thinks it means. That's…I would start there. And I would pin her down this time because postmodernism sounded like an interesting idea when it was first proposed. And then suddenly it couldn't really be defined in the dance and seemed inappropriate for the breadth of work and ideas that were happening. All of this is postmodern just because modern already happened? Is modern over? Wasn't the title “modern” slippery enough to live for more than…what? Probably it only lived for about 30 years, really, as a…as a name of a movement, but I think as an idea for a title — modern, new, experimental — all those words that were rampaging around the early modern dance as we now call it were all good enough to explain that the work was going to stay current. That it wasn't going to, in fact, become classical and be only the heritage from the past. So, maybe we don't have a word that will do that. But certainly postmodern only suggests post-, postmodern instantly, you know, and, you know, après moderne, you know, whatever you're going to come up with next to… Once you start doing that you're lost in an academic field of titles, which might perhaps be better described just by the dates.

Myriam Van Imschoot I agree.

Steve Paxton I mean, non-classic dance from 1940 to 1950, you know?

Myriam Van Imschoot Or all just “contemporary dance” because that's what it was when it issued…

Steve Paxton Yeah, whatever. But once you name a thing, you see, once…it would tend to stick to Graham, you know. It would tend to stick to whoever was considered the exemplar. And that's not fair, either to the artist or to the public. So, in a way, we have a semantic problem, don't we?

Myriam Van Imschoot But Steve, what makes then… What does it mean: the Americanness,…this soil for improvisation to emerge, to rise?

Steve Paxton Well, I don't think it did emerge there. I think that it is very strong there right now or was very strong there. I'm not sure it is so strong anymore.

Myriam Van Imschoot I agree with that.

Steve Paxton I don't really actually see it happening so much over there. And it might be that… When was it strong there? It was strong there in the '70s. Because I and my friends were managing to survive and make a living on it. I guess that's pretty strong. Strong enough. But, I don’t know. We're into a pretty big arena right now, aren't we? We're talking about whole cultures. And…

Myriam Van Imschoot I know.

Steve Paxton We do get there and the whole psychologies of whole peoples. I mean, this is pretty imponderable stuff. I think America has a…I think it has a romance with itself, of still being the pioneer country and obviously in that kind of life improvisation is much more obvious. That you are improvising is much more obvious. Once you get huge concentrations of urban populations, it looks like improvisation tends to go away, and it looks like culture and civilization exists because of lack of improvisation and then improvisation becomes a very dirty word. You know, you're just improvising. You don't really know what you're doing. So in other words, you don't have a map. You don't have a plan, in your…in your…in the situation. Your thought forms are not very deep, I think these are the implications. But one thing that America seems to be contributing, and I'm sure… First of all, the whole idea of modern dance had, at least by implication, the idea that improvisation was an important aspect of it. So that's about 100 years of thinking, and I think it started in Europe and bounced over to America, where it was romantically indulged…I don’t know…

Myriam Van Imschoot So, a concrete question because…

Steve Paxton I just want to go a little further with this.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton It was romantically indulged, and then the whole construct of dance started to change, which maybe we can kind of look toward mid-century, you know, at Cunningham, the shock of Cunningham’s structures and premises, but also around that time, the kinesiologists and the fact that they started to build up in the dance community an appreciation for anatomy and physiology and chemistry of the body and all of this, so that by this end of the century, there are a fair number of people with a lot of information about the body in the art form. You don't ask painters to understand physiology, you know, although their art also relates to movement. In fact, all the arts are based in movement and the body. So, they're… The sciences underlying dance have become more adventurous and more available, and instead of being, yeah, left to the Academy, have come out into the field, where dance is. And so, you have the whole Body-Mind Centering or Feldenkrais or any of those are much more available now as ways to think and ways to influence movement and choreographic choices, you know, we're… It's possible to see the performance through a different lens than perhaps we saw through 50 years ago. And, you know, are the dancers working with their organs, for instance, or are they just working with their muscles and skeleton? Where, what is their mindset? The mindset has shifted clearly into a much deeper understanding of anatomy and physiology and kinesiology, and all the other -ologies that had to do with the body. And I think that has been a contribution and has, in a way, presented Europe and the Orient with new mindsets to substantiate the idea that you can’t just look at dance as bones and muscle, and smiles and mascara anymore, you know. That it's a little bit more interesting than that. And so the field opened up. And so, once a field opens up, once you have a new area to explore, you're exploring. You're not presenting the old paradigms. Except in quotes, as you said. Now, the work that you were talking about, where so much of it was made up of, in a kind of academic way, of quotes from various sources shuffled in such a way as to create the message. That's a kind of decadent art, I think, in a way. And the work that's not decadent is not fully developed yet. So, it can't be considered a mature form, either. But it is maturing. And on the other hand, the decadence is keeping in front of us, they…and that's such an awful word. Maybe I should find a better word, but the quote… “quoting arts" are keeping in front of us some of the subject matter that we do see shuffled into our lives just because of the way life is now. I mean, if you look at an evening’s worth of TV, you’re apt to see any number of things shuffled together. And so it's become a…life has become much more mixed medium than it seemed at the beginning of the century to be. That’s what I think…something like that is what I wanted to say. What were you going to…

First improvisations45:29

Myriam Van Imschoot When did you improvise in performance in front of an audience?

Steve Paxton 1967.

Myriam Van Imschoot 1967. That’s where you would date your first improvised [performance]?

Steve Paxton I went on a tour by myself and one of the pieces had an improvisation in it. And by 1970, I had decided that maybe I should just look at improvisation because I really didn't understand it. And I felt like there were plenty of people looking at choreography, and, you know, the technique - that didn't need help -, but improvisation was just one of these confounding things to think about. So what were we doing? Why did we think we could do it? Who told us what it was? How did it get defined for us?…kind of thing.

Myriam Van Imschoot I'd like to go on on that track. But just to juxtapose that with another question: When was…when was the first improvised performance, I mean, that you were conscious of being improvised that you saw? Did that precede your own?

Steve Paxton I think probably. Probably, I would look, the first ones that I realized were improvised, anyway, because dancers had been doing this for a long time but not telling anybody…was Simone Forti’s first performance.

Myriam Van Imschoot Which one are you thinking of?

“Forti’s simply typed handbill for her performance event titled “Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things, by Simone Morris,” listed Ruth Allphon, Carl Lehmann-Haupt, Marnie Mahaffay, Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, and herself as participants, along with a “tape by La Monte Young.” Forti’s works were performed twice, on Friday, May 26, 1961, and on Saturday, the 27th. Her event was one of a series organized by Young, with Yoko Ono, in Ono’s loft space at 112 Chambers Street in downtown Manhattan. Ono intended to make her loft a performance space that was an “alternative to classic concert halls uptown,” according to Midori Yoshimoto. One of several similar events during 1960 and 1961, the Chambers Street series represented an early bringing-together of experimental music and other performance practice that shared in common a concern with the score after Cage, a pared-down approach, and an emphasis on the single “event.”” Meredith Morse, Soft is Fast: Simone Forti in the 1960s and after, The MIT Press, 2016, 84-85. ↩

Steve Paxton The very first New York performance…the Chambers12 Street studio performance.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yes. The Yoko Ono loft?

Steve Paxton Yoko Ono’s space, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot Do you remember the title of that?

Steve Paxton And there were…she had, she had five…no, I don’t. The title of the evening?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton It was Work by Simone Forti, I suppose.

Myriam Van Imschoot So that must have been nearly 1960 or '61.

Steve Paxton Yeah, '61, I believe.

Myriam Van Imschoot Interesting that, talking to Simone…

“Halprin was Forti’s mentor in dance and movement work from the mid-to late 1950s in the San Francisco Bay Area, at a time when Forti was painting but looking for something else; she found it in Halprin’s work with the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop. In 1959, Forti moved with her then-husband Robert Morris to New York City, bringing with her what she had learned from Halprin’s anatomically based movement practice, kinesthetics or kinesthetic awareness.” Meredith Morse, Soft is Fast: Simone Forti in the 1960s and after, The MIT Press, 2016, 4. ↩

Steve Paxton She was coming from Anna Halprin.13

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. And I talked about it and asked her when did you improvise the first time in front of an audience? I mean, just the same question I'm asking to everyone. And she said, that must have been the beginning of the 70's. I mean, it's not about whether that’s correct or not, it's just useful to know how someone…

Steve Paxton How it's perceived. Well, I was at that time a Cunningham dancer. So, I was doing about as defined a movement flow, you know, for an hour and a half, as is possible to have to do. And Simone's work had a structure, maybe she wouldn't consider it an improvisation because there was actually something to do. There was a task. But inside that task, you had to improvise as a performer. I was in the performance. So, I had to do things with my mind in that performance that I did not have to do with Cunningham. And that was for me the beginning of improvising. But I mean…

Myriam Van Imschoot So that may have been your first improvised contribution to performance.

Steve Paxton Yes, yeah. So, when did I first started improvising? [laughing] I suppose it was there. But in a way, it was her improvising through my body, you know. She was making me do it. So I didn't feel my self was doing it. I felt like I was doing it because I was… So maybe it was an improvisation on some funny level. Maybe task is a better word for it. I had a form to fulfill…however I chose to fulfill it. But nonetheless, something to fulfill.

Myriam Van Imschoot How did you get to know each other?

Steve Paxton Simone?

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah.

Steve Paxton I think all of us met at the Cunningham studio.

Myriam Van Imschoot And she was taking a class?

Steve Paxton She was taking Cunningham classes. As was I.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. Maybe she would have said that. Because Robert Morris knew Robert Rauschenberg very well, that's, that's the way she must have run into you, in that circle of people.

Steve Paxton Well, that was definitely a later aspect. But the first meeting was before Morris. Not before Morris, but before I knew Morris, or Bob Rauschenberg knew Morris, and, and I think before she knew Rauschenberg. So, yeah, it was there. I can recall her in those days.

Myriam Van Imschoot She did have a lot of improvisation practice because of the Anna Halprin work, where sort of a division between researching and dancing and performance was very undefined. So that was like a huge extended workshop feeling. And she, when she left San Francisco, she felt this inclination to break with that experience very much. So, she would define most of her work in the '60s, as something moving out of the orbit of improvisation as she had been associated with that work. And going indeed, more into…

Steve Paxton …structures.

Myriam Van Imschoot Structures, tasks, the you know, the Huddle or these kind of pieces like See Saw.

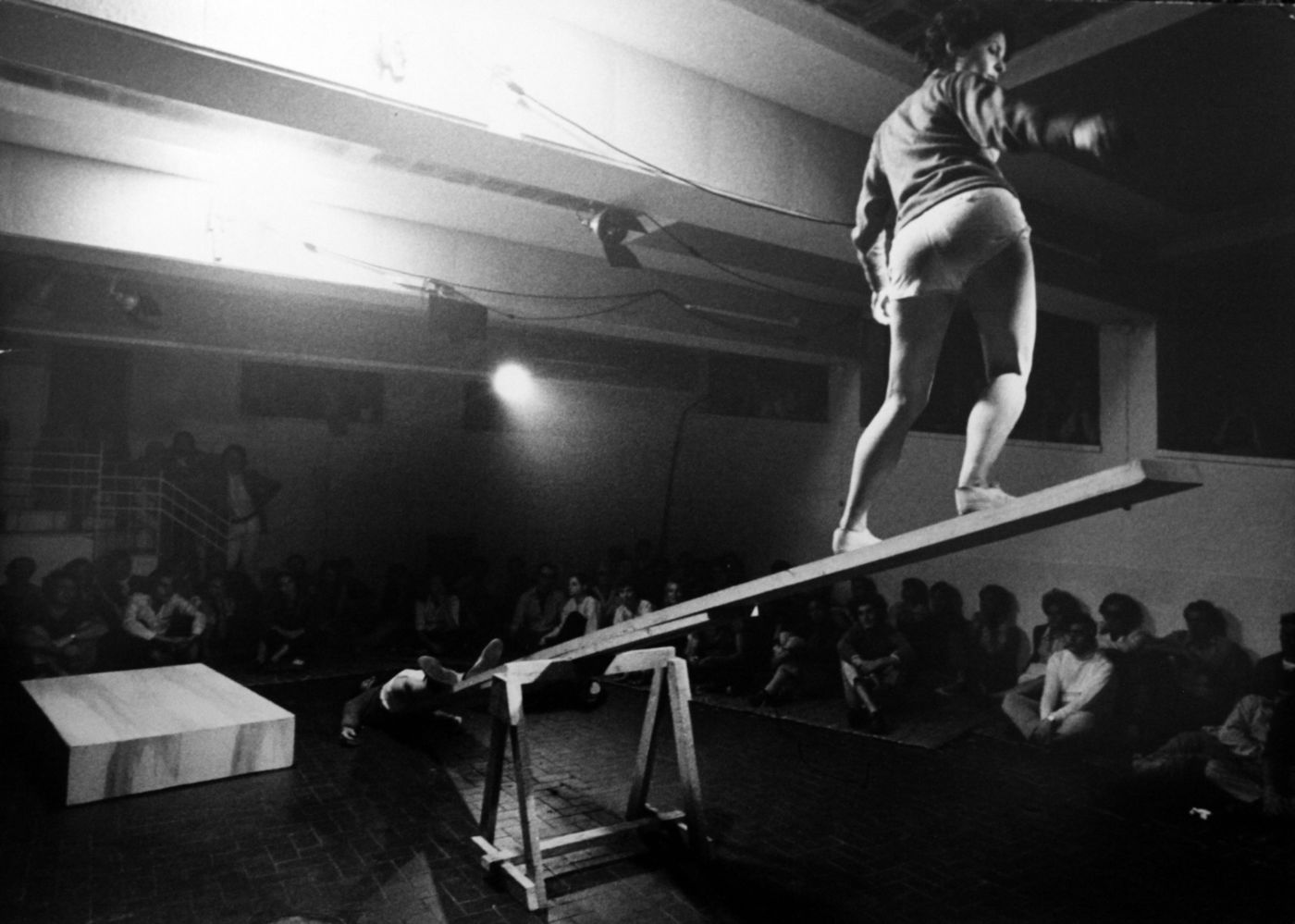

Simone Forti. See Saw from Dance Constructions. 1960. Performance with plywood seesaw. Duration variable. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Performed by Simone Forti and Steve Paxton at Galleria L'Attico, Rome, 1969. Image: © 2020 Claudio Abate, courtesy of Simone Forti and The Box, LA.

Steve Paxton Yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot And her coming back to it, to that heritage, or to that background was then in the late '60s, beginning of the '70s. So she feels that somehow the '60s, to her, were much more conceptual in orientation, hadn't been dealing that extensively with improvisation at least from her point of view.

Steve Paxton Well, we’re talking about Huddle…

Myriam Van Imschoot And that later she stopped doing…

Steve Paxton Scramble I believe, the Slant Board. These works to her may have been structurally-oriented. To me, they were improvisational forays because of where I was coming from. So, I mean, there was no meter. [laughing] There was no count. You didn't know where all your limbs were supposed to be at every particular count, you know, through 45 minutes of dancing. So, you can imagine the kind of abyss that it seemed like. There was no foothold, no toeholds, no armholds. So, maybe improvisation is different things depending on where you've come from. She had just come from a much looser…

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah… That’s, so… That makes it so hard to define it.

Steve Paxton Maybe that's great to know.

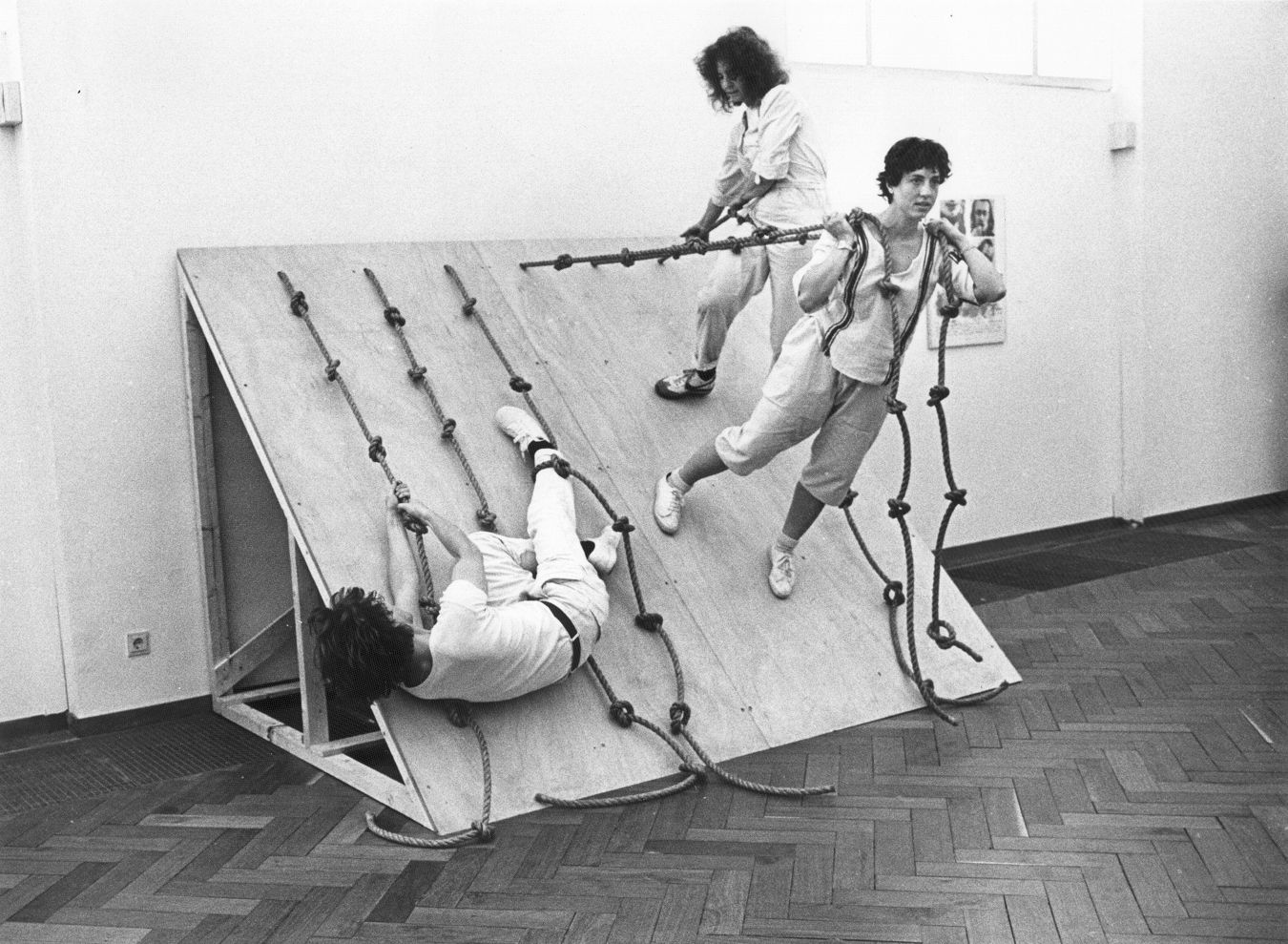

Simone Forti. Slant Board from Dance Constructions. 1961. Performance with plywood and rope. 10 min. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Committee on Media and Performance Art Funds. © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Performed at Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, 1982. Image: © 2020 Stedelijk Museum, courtesy of Simone Forti and The Box, LA.

Myriam Van Imschoot Because it’s really perspecti… I call it “perspectival.” Because it just depends, indeed, what your experience has been so far and just opening up the space for things to decide in is already improvisational in nature and the opening of that space is for someone, you know, maybe a huge thing if it's already some elements variable, as opposed to someone else who went for the whole open space. They would say well, you know, that's, you know, that's just not improv, you know.

Steve Paxton Yeah, yeah.

Myriam Van Imschoot Like a ballet dancer in the Ballet of Flanders said…well, we use improvisation, too, in performance, you know, because, at a certain point, we could make some selections in terms of movement quality or little things like that, and for her, it's, you know…

Steve Paxton Well, in fact, you know, the very best dancers of the classical type that I've seen, seem to be improvising. And I don't know whether it's a state of mind that we're talking about, I know that they've done the steps maybe thousands of times, but they find something new within the structure, and essentially, that's all that you're doing. Whether it's a structure that's, that's extremely defined, or whether it's a structure that's not defined.

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s finding the margin of that structure and…

Steve Paxton Yeah, I mean, if you're given, if you're given a time and a place in which, you know, for 20 minutes something's going to happen, you know, but you don’t know what it is. Still, there is a structure there. The space is defined and the time is defined. Within that, you're making choices that normally would devolve on a choreographer. So each person is choreographing their own way through the situation relative to other choreographies that are also happening. And it's a question of, you know, now we're getting back to that image that I said about the group mind that people are able now to inhabit, but at that time, it was very difficult to inhabit. So you actually needed something like a Huddle to help be the group mind for, you know, to take the place of group mind. After you've been through a number of Huddles and Scrambles and Slant Boards and working outside and working inside and on roofs and god knows what, then maybe another step is possible.

Myriam Van Imschoot Yeah. So, you could see things like tasks but also game structures as like a predecessor for…

Steve Paxton Yeah, a step, a step on a path toward “get rid of the game, but continue to play." Get rid of that particular game and see what kind of game actually evolves.

Myriam Van Imschoot Terminologically, sometimes, it's really a big mess. And when you look at the first half of the '60s, and it's just like task, the notion of chance, indeterminacy, game structures, rule-based…

Steve Paxton But in terms of the way we've just described it, it makes a lot of sense. Because then indeterminacy, for instance, is a situation in which you know what the material is, but you don't know when it's going to happen. It's not determined. The ability to create movement would be something that would come out of coping with the various tasks that you're given but which aren't too defined. You're supposed to get from here to there, but we don't care how you do it. You know, you’re supposed to get through this 20 minutes, but we don't care what you do. So yeah, gradually you assume more and more responsibility, essentially, for yourself and less responsibility is taken over by structure, or by hierarchy, or by… By structure, I mean, choreographic structure. By hierarchy, somebody telling you what to do. Or from the past, which would be the examples that everybody has in common, that we know how to communicate with. So, we're stepping into a funny arena socially because it's like a very loose party, as opposed to a very proper party. A very proper party, everybody knows how to behave, how to dress, and you know, their codes, and all of them mean something, and if you don't adhere to them, you're really out on the fringes. And you know, you'll be ostracized or ignored a little bit or you somehow won't be on the inside of something. We managed to get beyond that, and to allow… And this was, I mean, look at the politics of the 60s. Look at this. The social hierarchies that broke down during the 60s, you know. All of that was happening at once. And a lot of it was in rebellion against. It seemed like the codes were leading us in directions that we didn't really want to go to, essentially, the Vietnam War, racism, continued racism, other things. So, it was…it was worth questioning those structures and pointing to what was actually happening as opposed to the kind of self-created propaganda about what was happening. And new structures have evolved. And I think one does look for structure, finally…but one’s real structure. One doesn't want propagandistic or…Oh god…

Myriam Van Imschoot I take a glass of water in the meantime.

Steve Paxton While I’m struggling here, you’re going to go take a shower. [laughing]

Myriam Van Imschoot Or take a bath.

Steve Paxton Yeah, you know, feel free, makes yourself at home. [raises his voice to reach the other part of the room] That, that if you question the directions that the structures lead you to, then you question the validity of the structures to some degree, and this leaves you open to finding new ways to relate. And I think all of that was successfully transited, and then there was a backlash against it, and the Lincoln Kirstein articles that we talked about before came after a huge amount of social and artistic upheaval. But quite necessary questions, really. Do we really want certain races in the back of the bus and certain other races in the front of the bus? Is this really what…, is this really what our structures have led us to? Do we want this to be happening? You know, I don't think it is productive. I think, in a way, survival for a few at the expense of many others is a very unstable structure. And…

Myriam Van Imschoot It’s a huge issue on all levels of society, life, making art.

Steve Paxton All levels, all levels.

Myriam Van Imschoot It makes so much sense that the 60s was doing the exploration for trying to loosen up structures and see what other structures could be more…

Steve Paxton And what other structures are available. I mean, America is a very isolated place and a very new place, [a] new culture based in a new space. So the arrival of the Eastern arts, meditation, yoga, martial arts, you know, these very highly developed and superior forms of physical work - meditation might not be considered physical. Of course, it is, but not in the sense that we normally mean it. We had to mean things in a new way in order to achieve these ideas. It's a struggle for ideas, and the question of position relative to ideas where, “How do you relate to them?"

Myriam Van Imschoot Shall we take a break for a couple of minutes? You wanna?

Steve Paxton No, no, let's go on to something else.

Myriam Van Imschoot 1967. You have to tell me about that.

Steve Paxton That improvisational moment? Well, it was an improvisation in which…I can't remember what was on the voice tape now. Well, this was the situation. There was a typist. There was a tape machine. And there was a dancer. I was the dancer. And the typist was to transcribe the material on the tape. And I had to run the tape machine so that it didn’t…so they didn't get lost. So, the typist was controlling the dancer because the dancer also had to be the tape machine technician.

Myriam Van Imschoot Wait a minute.

-

Steve Paxton’s thoughts on the pressure and doubts when making “choreographic work” seem to come from a specific situation, although in retrospect it is unclear which. Was it the invitation to Mouvements (2003) at the Opera de Lyon, where Paxton would perform a duet with Trisha Brown called Constructing Milliseconds to music of Ammon Wolman in a program with work of Mathilde Monnier and William Forsythe for the Ballet d’Opéra. Or, was it an invitation to perform New Work at the Impulstanz Festival in Vienna (rather than proposing new choreography, Paxton invited The Lisbon Group for improvised group performances on 12, 14 and 15 July 2002)? Point is that Paxton can brood a long time over invitation before conjuring response. This interview cluster ends with an example of Ash, a piece that premiered in 1997 (deSingel, Antwerp) mixing in a then recent experience with his father’s death and the circumstances of his burial. ↩

-

Steve Paxton was a key player in the improvisation revival in Europe in the '90s. Especially the group improvisations marked the sign of the times as open events prone to experiment with other production and presentation formats. Honing unexpected encounters, these assemblies showed the larger need amongst a whole range of dancers, choreographers, musicians and artists to meet for exchange and collaborative synergies. This concurred with a new phase of internationalization, institutional growth of dance festivals, a stronger questioning of artist career as solidified on choreographic signature alone, and the tendency to look back to the legacies of the 1960s and 1970s in search of other information and models. Taking the participations of Steve Paxton as a lead, the weave of initiatives in Europe shows a broad range: he participated in the Improvisation Evening 1995 at Klapstuk in Leuven and the Night of Improvisation in Frascati Amsterdam in 1998, both events coordinated by Katie Duck. He was a guest at Crash Landing in Vienna 1997, curated by Meg Stuart, David Hernandez and Christine De Smedt, and again in the Festival On the Edge, curated by Mark Tompkins in three different cities, Paris, Strassbourg and Marseille. He danced upon invitation with Frans Poelstra as well as in the closing group improvisation event of Danças Na Cidade in 1999. It’s about the latter evening he speaks so fondly in this interview. The group improvisation in Portugal included Silvia Real, Teresa Prima, Vera Mantero, Boris Charmatz, Xavier Le Roy and Frans Poelstra, later referred to as The Lisbon Group. ↩

-

Paxton is referring here to the improvisation evening at Danças na Cidada, on 28 November 1999. ↩

-

Between 1962 and 1964, a diverse group of choreographers, dancers, composers, musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists were gathering for a series of concerts at the Judson Memorial Church located at Washington Square Park, New York City. Although short-lived, this movement, called Judson Dance Theater, marked a radical reinvention of dance, choreography, and performance and has changed their history ever since. Although its style was varied and often eclectic, its main traits were an investigation into the movements of everyday life, undoing dance from its modern, theatrical, and structural conventions. Amongst its main participants were Trisha Brown, Lucinda Childs, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, David Gordon, and Deborah Hay. Of importance here is that the Judson Church Theater members would appear in each other’s works and thus nurture each other’s artistic practices. Such an unorthodox approach, which counteracted the way the modern masters usually would work with their dancers, led to the possibility to develop multifaceted embodiments and the versatility of lending one’s body to very different sorts of works, aesthetics, and signatures. ↩

-

Lincoln Kirstein (1907-96) was an influential American arts patron, writer, and curator, who dedicated his life to the modernization and institutionalization of American ballet. Together with George Balanchine (1904-83) he founded the New York City Ballet in 1946. He was also involved in the development of the School of American Ballet, which he led from 1940 till 1989. About the difference between a choreographer and a ballet master Kirstein writes in his book Movement and Metaphor from 1971 the following: “Let us distinguish here between choreographers and ballet masters. Such nomenclature is hardly binding; terms overlap, but a distinction between respective services can be almost precise. […] Choreographers put steps together from a syntax they receive; from this, they compose rather than invent dances. […] Choreographers are simple carpenters; ballet masters are cabinetmakers; some of them – the most gifted – sculptors. Ballet masters have the capacity to conceive unusual or novel movement beyond the range of the academy. Not only do they increase repertories with memorable work, but they also extend the academic idiom by new orientations and analyses.” Lincoln Kirstein, Movement and Metaphor: four centuries of ballet, Pitman, 1971, 16. For an analysis of the debate between the ballet-based norms of Lincoln Kirstein and the modern dance values, see the polemic between Lincoln Kirstein and critic John Martin in “Abstraction has many Faces: the Ballet/Modern Wars of Lincoln Kirstein and John Martin” by Mark Franko in Performance Research 3(2), 1998, 88-101. ↩

-

The use of scores started as early as the beginning of the 1960s when Steve Paxton integrated elements that were picture-scored in the trio Proxy (1961) and the solo Flat (1964), both pieces created and presented in the frame of Judson Dance Theater. The photo sequences were to be interpreted by him or other performers and took the choreographer out of designing a dance and legitimized something that dancers do all the time, which is to give the choreographer movement suggestions. Photo scores were also used in Jag Vill Gärna Telefonera (1964), a duet with Robert Rauschenberg that premièred in Stockholm and later in the 1980s for the pieces Ave Nue (1985) and Audible Scenery (1986) with Extemporary Dance Theater, which shows that the interest in photo-generated movement resurfaced as a compositional tool and interest throughout his work. ↩

-

Sally Banes has described The Grand Union as follows:“The Grand Union was a collective of choreographer/performers who during the years 1970 to 1976 made group improvisations embracing dance, theatre and theatrics in an ongoing investigation into the nature of dance and performance. The Grand Union’s identity as a group had several sources: some of the nine who were its members at different points had known each other for as long as ten years when the group formed. They had seen and performed in each other’s work since the Judson Church days. Most had studied with Merce Cunningham, and three had danced in his company.” Sally Banes, “The Grand Union: The Presentation of Everyday Life as Dance” in Terpsichore in Sneakers, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1980, 203. Amongst its members were Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, Douglas Dunn, Barbara (Lloyd) Dilley, David Gordon and Becky Arnold. ↩

-

The Mind is a Muscle is an evening-length performance, which premiered at the Anderson Theater in New York City on April 11, 1968. It included some works which had been performed before, such as The Mind Is a Muscle, Part 1 (which would later get the title Trio A) at Judson Church in 1966. The piece comprised eight different parts and nine interludes, including dance sections danced in different constellations, her piece Trio A, conversations, songs, films, and a lecture by Rainer herself. Steve Paxton was part of the cast. In the statement on the program leaflet, Rainer writes: “It is my overall concern to reveal people as they are engaged in various kinds of activities – alone, with each other, with objects – and to weigh the quality of the human body toward that of objects and away from the super-stylization of the dancer. […] The condition for the making of my stuff lies in the continuation of my interest and energy. Just as ideological issues have no bearing on the nature of my work, neither does the tenor of current political and social conditions have any bearing on its execution. The world disintegrates around me. My connection to the world-in-crisis remains tenuous and remote. I can foresee a time when this remoteness must necessarily end, though I cannot foresee exactly when or how that relationship will change, or what circumstances will incite me to a different kind of action.” Yvonne Rainer, Work 1961-73, The Presses of the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and New York University, 1974, 71. ↩

-

American dance ideas and practices exercised a big influence on the European dance scene through various choreographers and improvisers teaching at the SNDO Amsterdam (from the '80s onwards) and EDDC Arnhem (from 1989 onwards). The development of somatic practices for performance, improvisation and choreographic strategies was amongst others disseminated by Eva Karczag, Jennifer Monson, Stephanie Skura and Mary Overlie. In the same line we could mention Dartington College, where Mary Fulkerson upon arrival in 1973 invited a line of American colleagues to teach with her. Contredanse was founded by Patricia Kuypers and had a pedagogical mission outside of regular art education that contributed to the dissemination in French artist circles. In 2009, Jeroen Fabius, currently artistic director of the DAS Choreography program in Amsterdam, published a book looking back on 30 years of dance education and development at SNDO, the School for New Dance Development, in Amsterdam. The publication includes contributions by Steve Paxton and Lisa Nelson. Jeroen Fabius (ed.), TALK/1982-2006, international theatre & film books, 2009. ↩

-

Cynthia J. Novack, Sharing the Dance: Contact Improvisation and American Culture, University of Wisconsin Press, 1990. ↩

-

Sally Banes, Democracy’s Body:Judson Dance Theatre 1962-1964, Duke University Press Books, 1983. ↩

-

“Forti’s simply typed handbill for her performance event titled “Five Dance Constructions and Some Other Things, by Simone Morris,” listed Ruth Allphon, Carl Lehmann-Haupt, Marnie Mahaffay, Robert Morris, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, and herself as participants, along with a “tape by La Monte Young.” Forti’s works were performed twice, on Friday, May 26, 1961, and on Saturday, the 27th. Her event was one of a series organized by Young, with Yoko Ono, in Ono’s loft space at 112 Chambers Street in downtown Manhattan. Ono intended to make her loft a performance space that was an “alternative to classic concert halls uptown,” according to Midori Yoshimoto. One of several similar events during 1960 and 1961, the Chambers Street series represented an early bringing-together of experimental music and other performance practice that shared in common a concern with the score after Cage, a pared-down approach, and an emphasis on the single “event.”” Meredith Morse, Soft is Fast: Simone Forti in the 1960s and after, The MIT Press, 2016, 84-85. ↩

-

“Halprin was Forti’s mentor in dance and movement work from the mid-to late 1950s in the San Francisco Bay Area, at a time when Forti was painting but looking for something else; she found it in Halprin’s work with the San Francisco Dancers’ Workshop. In 1959, Forti moved with her then-husband Robert Morris to New York City, bringing with her what she had learned from Halprin’s anatomically based movement practice, kinesthetics or kinesthetic awareness.” Meredith Morse, Soft is Fast: Simone Forti in the 1960s and after, The MIT Press, 2016, 4. ↩